THE BARBIE MOVIE BACKLASH: The problems with fast fashion & consumerism

As the world celebrates Barbie, a global cultural icon from the 2023 film release, it is important to address the excessive waste generated by the movie’s fevered fandom—such as toys, fast fashion, and the resulting carbon footprint (Peradze, 2023). The film’s release increased demand for the doll and contributed to immense quantities of waste. The plastic and paint materials used to produce the toy, along with the associated carbon emissions, have raised alarms as the environment is similarly affected and compromised. The production of the Barbie movie itself contributed to a worldwide shortage of fluorescent pink paint. Rosco, a supplier specializing in paint designated for film productions, ran out of the product before the film was completed (Plastic Reimagined, 2024).

In this story, we will dive into how Barbie, one of the highest-grossing movies of all time, continues to receive both praise and criticism, even more than a year since its global release. While some have applauded the Barbie film’s aggressive and efficient marketing tactics, the environmental community was outraged by the launch of a “planet in a thick pink blanket.” Today, attention remains high, particularly due to the waste its merchandise collaborations introduced during the film’s promotion. The film’s marketing approach extended into personal care, fashion, and other industries. This resulted in complex packaging materials that inhibited recyclability and reduced sustainability (Waldeck, 2023).

Barbie Movie outfit idea @Concealerandaprayerlife

Barbie Movie outfit idea @Concealerandaprayerlife

PART 1:

The Fast Fashion Industry

What is it and why is it harmful?

There has always been criticism of how Barbie portrays the perfect woman, creating a standard that women cannot replicate in an imperfect world. It is hard for all women to be blonde with exaggerated body measurements. Barbie also symbolizes something more: “conspicuous consumption” (Mattel’s materialistic values). The marketing helped transform Barbie into an icon of consumerism. She taught young girls to become insatiable shoppers long before Instagram and TikTok celebrity influencers promoted glamorous living. The release of the Barbie film greatly contributed to this perception. For instance, owning just the blue-eyed doll was not enough. Young girls felt compelled to have her diverse doll friends, her multitude of career dolls, the multilevel Dreamhouse, the Corvette, and all those endless cute dresses and shoes. According to Mattel, more than 100 dolls are sold every minute, while a Barbie Dreamhouse (introduced in 1962) is sold every two minutes. Critics state that many young girls grew up to become shopaholics, trying to fill a void left by a Barbie-less childhood or living above their means, creating a lifestyle where they are never denied. This is clearly portrayed in the Barbie movie, with an excessive amount of merchandising from beginning to end (Singletary, 2023).

The Fast Fashion Industry

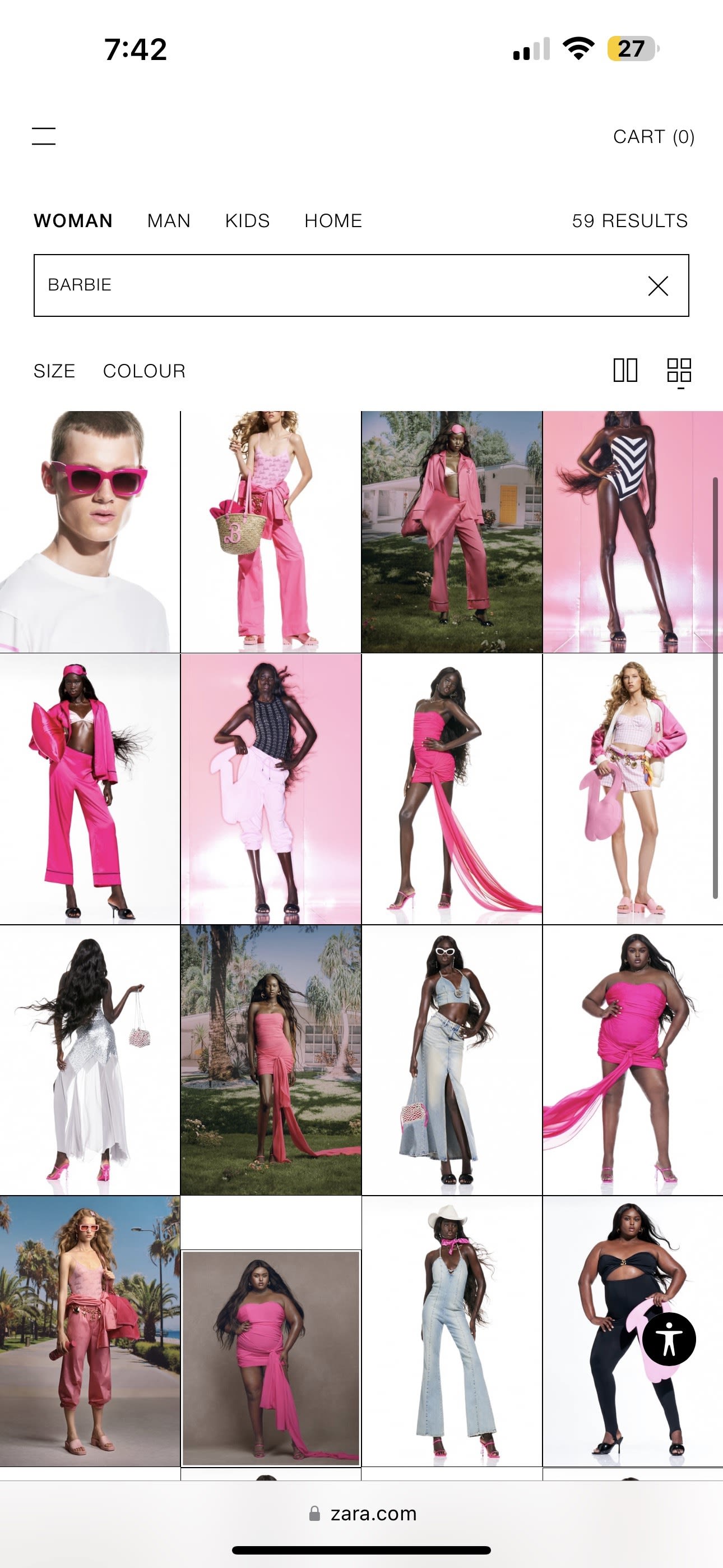

With the film’s release on July 21, 2023, Mattel’s (Barbie’s manufacturer) stock value increased approximately 4.5% since the start of the movie marketing campaign (Waldeck, 2023), which embraced different merchandise categories, including fashion. The fashion industry saw approximately 35 brands releasing tie-in merchandise. Some came from fast fashion brands such as Primark, Zara, and Boohoo (D’Souza, 2023; Henry, Laitala, & Klepp, 2019). Fast fashion brands designed official Barbie clothing lines. For example, NYX Cosmetics released a Barbie-inspired makeup set, and a Burger King in Brazil even introduced a pink barbecue sauce. Accessories such as necklaces or signet rings from Jewlr encouraged consumers to own something Barbie-pink to wear to the movie (Shaw, 2023).

Fast Fashion: A Buzz Expression

Fast fashion garment production leverages trend replication and low-quality materials (usually synthetic fabrics) to bring inexpensive styles to the end consumer. These cheaply made, trendy pieces have resulted in an industry-wide movement towards overwhelming amounts of consumption. Consequently, it has harmful impacts on the environment, garment workers, animals, and ultimately consumers’ wallets (Stanton, 2024).

Until the mid-twentieth century, the fashion industry ran on four seasons a year (fall, winter, spring, and summer). Designers worked many months in advance to plan each season and predict the styles they believed customers would want. While methodical, this approach catered to high society and was not mass-affordable. Currently, fast fashion produces about 52 “micro-seasons” a year—roughly one new “collection” per week (Stanton, 2024). According to Elizabeth Cline, a New York-based journalist and expert on consumer culture, this started when Zara shifted to bi-weekly deliveries of new merchandise in the early 2000s. Since then, it has been common for stores to maintain a towering supply of stock at all times, ensuring brands never run out of clothes. Fast fashion often replicates streetwear and fashion-week trends as they appear in real time. Companies can create new, desirable styles weekly, if not daily. This results in massive amounts of clothing and ensures that customers never tire of the inventory. Examples of fast fashion companies include H&M, Boohoo, Shein, Topshop, Temu, Zara, and others (Cline, 2013; Malhotra, 2024).

Why Is Fast Fashion Bad?

The fast-fashion manufacturing process results in garments being thrown away after only a few wears. Companies such as Topshop and Fashion Nova have started expressing concern about the “ocean of clothing” they churn out for profit. These brands earn millions of dollars by selling pieces cheaply. Additionally, garment workers are undoubtedly being paid below minimum wage (Stanton, 2024). As Lucy Siegle mentioned in her documentary The True Cost, “Fast fashion isn’t free. Someone, somewhere is paying.”

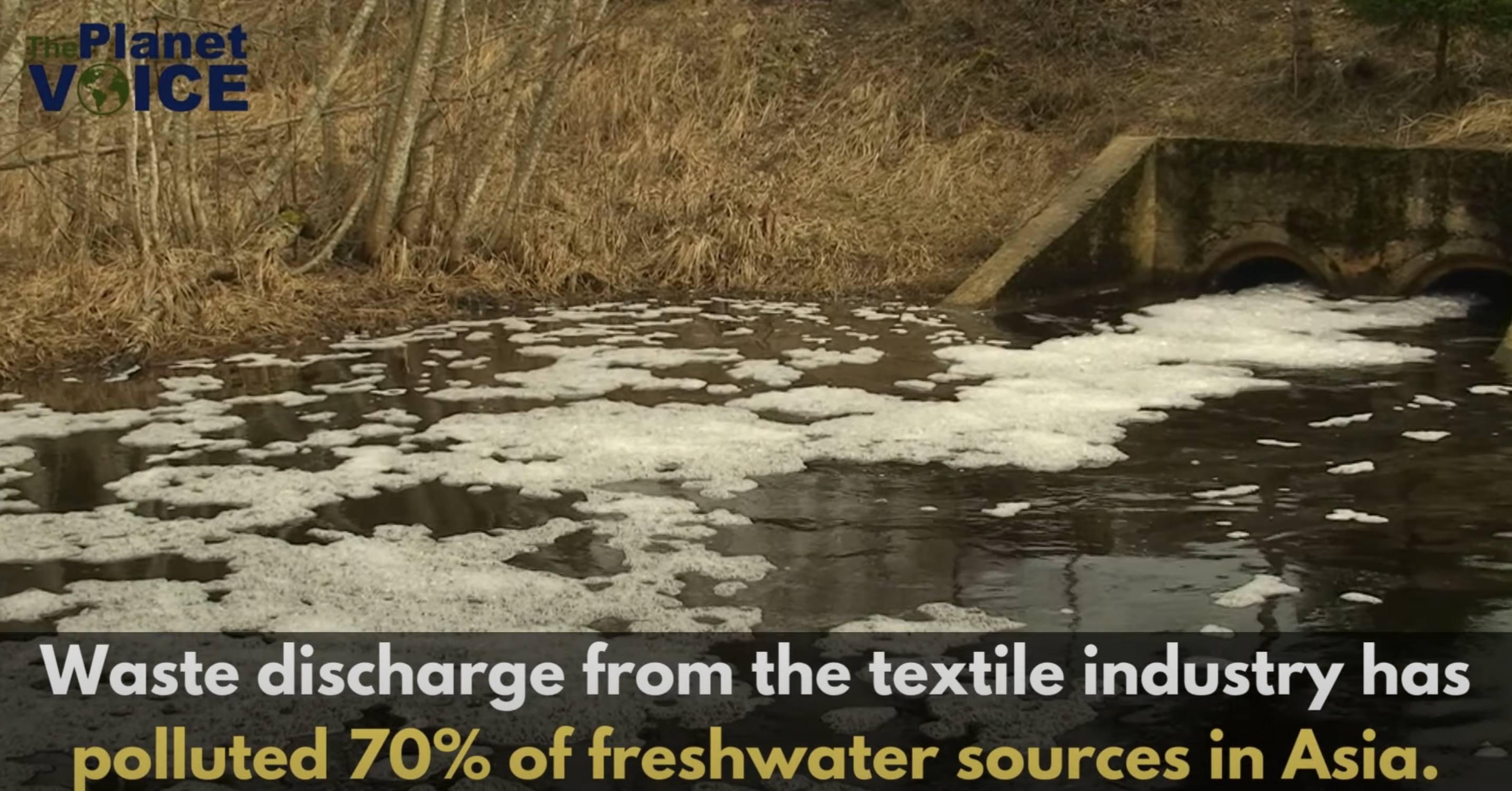

All elements of fast fashion—trend replication, rapid production, low quality, competitive pricing—have a detrimental impact on the planet and the people involved in garment production. Fast fashion brands use toxic chemicals, dangerous dyes, and synthetic fabrics that enter water supplies. In the United States alone, 11 million tons of clothing are thrown out every year. These garments are full of lead, pesticides, and countless other chemicals that do not break down. They sit in landfills, releasing toxins into the air and environment (Stanton, 2024).

In addition to environmental impact, fast fashion affects the health of consumers and garment workers. For instance, harmful chemicals such as benzothiazole (linked to several types of cancer and respiratory illnesses) have been found in apparel on the market today. Skin, the largest organ of the body, is the bridge between these poorly made clothes and consumers’ health. This danger also affects factory workers, local populations, and homes near fast-fashion production sites, where conventional textile dyeing releases heavy metals and other toxicants that impact the health of animals and nearby residents. Garment workers’ health is always in jeopardy due to exposure to these chemicals. They are underpaid, underfed, and pushed to their limits because few other work options exist for them (Bick, Halsey, & Ekenga, 2018).

As a recent Saturday Night Live sketch captured, knowledge of these abuses is not enough to slow fast fashion down. In a fake ad for “Xiemu,” a not-so-subtle combination of ultra-fast fashion giants Shein and Temu, a model asks, “How so cheap?” The narrator quickly responds, “Don’t worry about it.” Xiemu assures prospective customers its clothing is “not made with forced labor… no prisoners involved.” Despite all the red flags, when the narrator asks if the models would stop buying, they all say “no” (Malhotra, 2024).

PART 2:

The Barbie Movie's Influence on Fast Fashion

Barbie Film Influence on the Fast Fashion Industry

The problem with these fast fashion marketing campaigns is the amount of waste they produce. These trends and crazes come and go, and eventually the items get donated or tossed out. Additionally, many people are only interested in buying these products to post on their social media platforms. Once that is done, these items no longer serve much purpose (D’Souza, 2023). Thus, environmental concerns seem to have taken a backseat for most consumers in the post-movie craze. Pink fast fashion now seems more important than climate change (Shaw, 2023).

Even before the film, Barbie was always in style with all-pink outfits filling red carpets, countless social media posts with rosy themes, and the takeover of pink in street style. This trend started was referred to as “Barbiecore” after the movie’s release—the stylish doll whose brand identity is feminine and very, very pink. According to Lyst’s 2022 “Year in Fashion” report, Barbiecore was the top trend of 2022. It peaked in June of that year, when pictures of Margot Robbie as Barbie, clad in an all–hot pink Western outfit, were released. Her look went viral on social media, particularly TikTok, with a 416% increase in searches for pink clothing (Lang, 2023).

#Barbiecore Impact

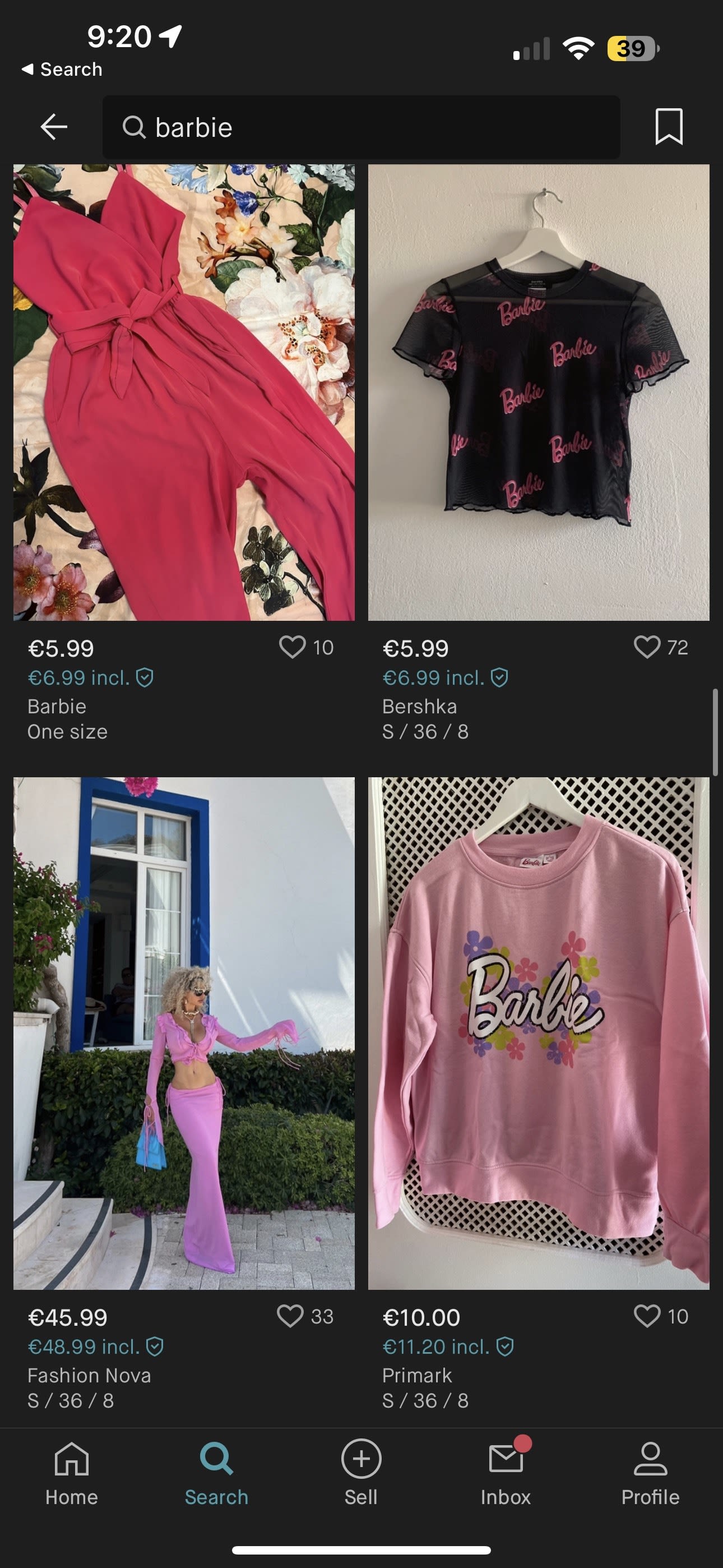

The Barbie merchandise craze caused an implosion, with heaps of clothes, dolls, and gear clogging up secondhand stores and landfills. Not all partnerships shown in the film are new plastic products. Jacqueline Durran, the film’s costume designer, partnered with the online secondhand platform ThredUp. Durran curated a #Barbiecore Dream Shop, which includes a collection of nearly 300 Mattel-looking styles priced from $9 to $500. Secondhand shopping is increasingly popular, and with Barbiecore being more of a style than branded merchandise, there is far more flexibility for consumers to leverage secondhand platforms to achieve the pink-on-pink look (Ettinger, 2023).

For instance, at $25, Barbie in a Pink Gingham Dress is a popular outfit that could easily be afforded when going to the movie. There is also the movie fashion pack of film outfits and accessories originally priced at $50 (dolls not included), now inflated to $75 (Singletary, 2023).

“As trend and ‘core’ cycles get faster each year, it’s becoming second nature for consumers to turn to fast fashion to get the look of the moment,” stated Erin Wallace, VP of Marketing at ThredUp. She continues, “We hope our #Barbiecore Dream Shop inspires fans everywhere to be mindful of how they participate in the latest trends without missing out on the fun” (Ettinger, 2023).

How fast fashion harms the environment - CBS Texas

How fast fashion harms the environment - CBS Texas

The History of

Barbie & Hyperconsumerism

Barbie's Influence on Fast Fashion

Ruth Handler, the woman who created the Barbie doll, was a savvy and style-forward businesswoman. She wanted to launch a doll that could give little girls the chance to envision their future dreams of being an astronaut, a doctor, or a fashion model. Naturally, she had the clothes to match. The element of fashion as a way of imagining the future was essential for Handler. Therefore, Mattel designed Barbie’s head to pop off easily to make it feasible to change her outfits. For Handler, it was important that Barbie represent what a woman could be, and that was reflected in the doll’s clothes. In her memoir, Dream Doll: The Ruth Handler Story, she wrote, “Even in her early years, Barbie did not have to settle for being only Ken’s girlfriend or an inveterate shopper. She had the clothes, for example, to launch a career as a nurse, a stewardess, a nightclub singer” (Lang, 2023).

Did you know? Fast fashion is the second largest polluter in the world after oil and gas.

Overall, the Barbie phenomenon encapsulates the inherent tension between any radical social movement and contemporary capitalism. Mattel’s primary goal remains its stock price and profitability. The conflict between feminist ideals and capitalist strategies results in cosmetic changes tailored to commercial interests, overshadowing the pursuit of genuine societal changes (The Squid Studios, 2024).

Thus, the Barbiecore trend and influence on fashion are central points of the doll’s marketing success and lasting hold in pop culture, as generations of children grew up to be adult consumers (with the ubiquitous association with the color pink). While the original Barbie doll did not have pink marketing, in the 1970s, Mattel shifted its marketing toward younger girls instead of teenagers. Making pink the main color for the doll’s brand identity helped with the new marketing strategy. Currently, the doll is synonymous with the color pink, and Mattel even has a copyrighted Pantone shade called “Barbie pink (219 C),” a deep and bright rosy hue (Lang, 2023).

With the film, the Barbiecore trend has spun out of control. The film’s “genius” marketing team indirectly triggered a temporary surge in clothing trends across the world, bringing back colorful, synthetic, early 2000s-inspired clothing. Little girls, teenagers, and their mothers had a sudden urge to wear bold pink, wanting society to see them as “cool.” Fast fashion and cosmetics brands jumped at the opportunity to capitalize on this temporary trend, quickly launching new collections. All of this painted the mountains of garment waste bright pink. This trend surge added tremendously to existing fashion waste piles in the Global South, worsening the effects of waste colonialism. Further, the high amounts of microplastic from these synthetic garments found their way back into consumers’ bodies. There was rapid turnover of these fast-fashion Barbie garments. Marketing and the fast fashion industry work to keep society blind to the problems accompanying participation in seemingly “innocent” trends (Rucha, 2023).

There are thousands of “Style it Like Barbie” videos on TikTok, which include hauls of “Barbie Looks” from popular retailers in the wake of the movie. The surplus of try-on videos makes it evident that the movie started a craze that further consolidates a consumer society. Fast fashion is in style. The continuation of these micro-trends shows how the consumerist movement is self-fueled, especially on platforms like TikTok and Instagram. Consumers love thrifting and capsule wardrobes—until they need a brand-new outfit to watch the Barbie movie. The rise of Barbiecore encourages consumerism on social media as it promotes the idea of buying into the whole Barbie package. From hot pink sweats to H&M and Primark, or from renting out the Malibu Ken Dreamhouse, capitalism helps consumers pursue the Barbie lifestyle (Shaw, 2023).

From Celebrity Fashion Figures to Fashion Trends

Barbiecore began with the rise of early 2000s celebrity fashion figures such as Paris Hilton, Nicole Richie, and Britney Spears, whose outfits, featured in tabloids, were hyper-feminine and often pink or glittery. It also inspired films such as Clueless, Legally Blonde, and Mean Girls. All of these featured female characters in bright pink, contributing to the trend’s popularity. In high fashion, the 2022 Valentino fashion show launched its hot pink Pantone shade, showing Barbie’s influence. The 2015 collection for Moschino also centered on Barbie iconography, with models walking the runway in blonde wigs, pink ruffled evening gowns, and pink sportswear (Lang, 2023).

According to Associate Professor Lauren Guerrieri, Senior Lecturer in Marketing at RMIT University, Barbie has set a trend for brands utilizing social justice to increase consumption of their products. The rise in consumerism has made consumption less sustainable. Previous trends, such as capsule wardrobes and thrifting, have been replaced by influencers buying single-use clothes to watch the Barbie movie. These single-use outfits will no longer be fashionable once the Barbiecore trend’s popularity dies down. Sustainability goals, once popular on social media, have been made redundant with Barbie’s marketing. “Pink fast fashion is now more important than climate change” (Shaw, 2023).

Emily Huggard, Assistant Professor of Fashion Communication at Parsons School of Design, explains that the trend has taken off because of its playfulness, which is appealing in a post-COVID world. It is similar to the “dopamine dressing” trend, which involves wearing brightly colored clothes that spark joy. Barbiecore is pretty, hot pink, and not too complex. A year before the film’s release, people were already purchasing all-pink outfits, with hot pink especially in demand, seemingly influenced by Robbie’s Barbie outfit. On TikTok, where the trend went viral in 2023, the hashtag #Barbiecore has racked up over 365 million views. Multiple Barbie fashion collaborations offering varying degrees of bubblegum and hot pink clothing and accessories—from brands ranging from Gap to Forever 21—emerged ahead of the movie. This new fashion appeal of wearing all hot pink lies in its financial accessibility. Barbiecore is a trend that everyone can participate in at some level. Hot pink is available at all price points. It’s an approachable trend, a luxury trend whose expensive minimalism relies on a cultural moment. Pink was seen at the Met Gala, on runways, marketed at different levels of the industry and at different prices—people can afford it more easily than other luxury items. They wear it to represent something (Lang, 2023; Shaw, 2023).

Mattel and the Paradox of Exploitative Labor Practices

Mattel’s “feminist” approach in the Barbie film and its slogan “to inspire & nurture the limitless potential in every girl” is paradoxical given the company’s long history of exploiting its largely female workforce in its Chinese factories. China Labor Watch, a nonprofit organization advocating for workers’ rights, has found that Mattel’s factories in China have a long history of labor abuses. These range from unpaid overtime, with workers putting in up to 80 or even 100 hours of unpaid overtime per month, to psychological violence such as verbal abuse, bullying, harassment, and threats, including sexual harassment (China Labor Watch, 2013).

There have also been reports of unsafe working conditions. Mattel factories were reported as unsafe, dirty, and overcrowded, with workers exposed to hazardous chemicals on a regular basis. Although Mattel has taken some steps to address these problems (such as creating “Home of Mattel” and a “Worker Hotline”), China Labor Watch reports these were only formalities and ineffective in representing workers’ rights, as most workers did not even know these resources existed (China Labor Watch, 2013). While Mattel has a code of conduct prohibiting labor abuses, the company has been repeatedly accused of failing to enforce that code and criticized for its lenience with violations in its factories (Mattel, 2020).

The Problem with Plastic

The Barbie Film and the Problem with Plastic

In Greta Gerwig’s movie Barbie, actress Margot Robbie plays the namesake plastic doll as she navigates Barbieland—a highly artificial, mostly plastic place designed for women’s empowerment and positivity. As the plot progresses, Robbie leaves her perfect, pink, plastic home to visit the challenging and imperfect “real” human world. As the movie rolled out worldwide, it sparked a surge in sales of Barbie dolls and accessories (the day a Margot Robbie Barbie went on sale, it became the number-one selling doll on Amazon), in addition to causing a surge in sales of synthetic, early 2000s-style fast-fashion clothing. These trends are about plastic, which is not good for individuals’ bodies, social justice, the climate, the environment, or wildlife. All are harmed by plastic pollution. Barbie, like all plastic toys, is harmful to human health because she is made of plastic. Children’s developing bodies are especially vulnerable to plastic pollution (Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023).

Toys, Chemicals, and Toxicity

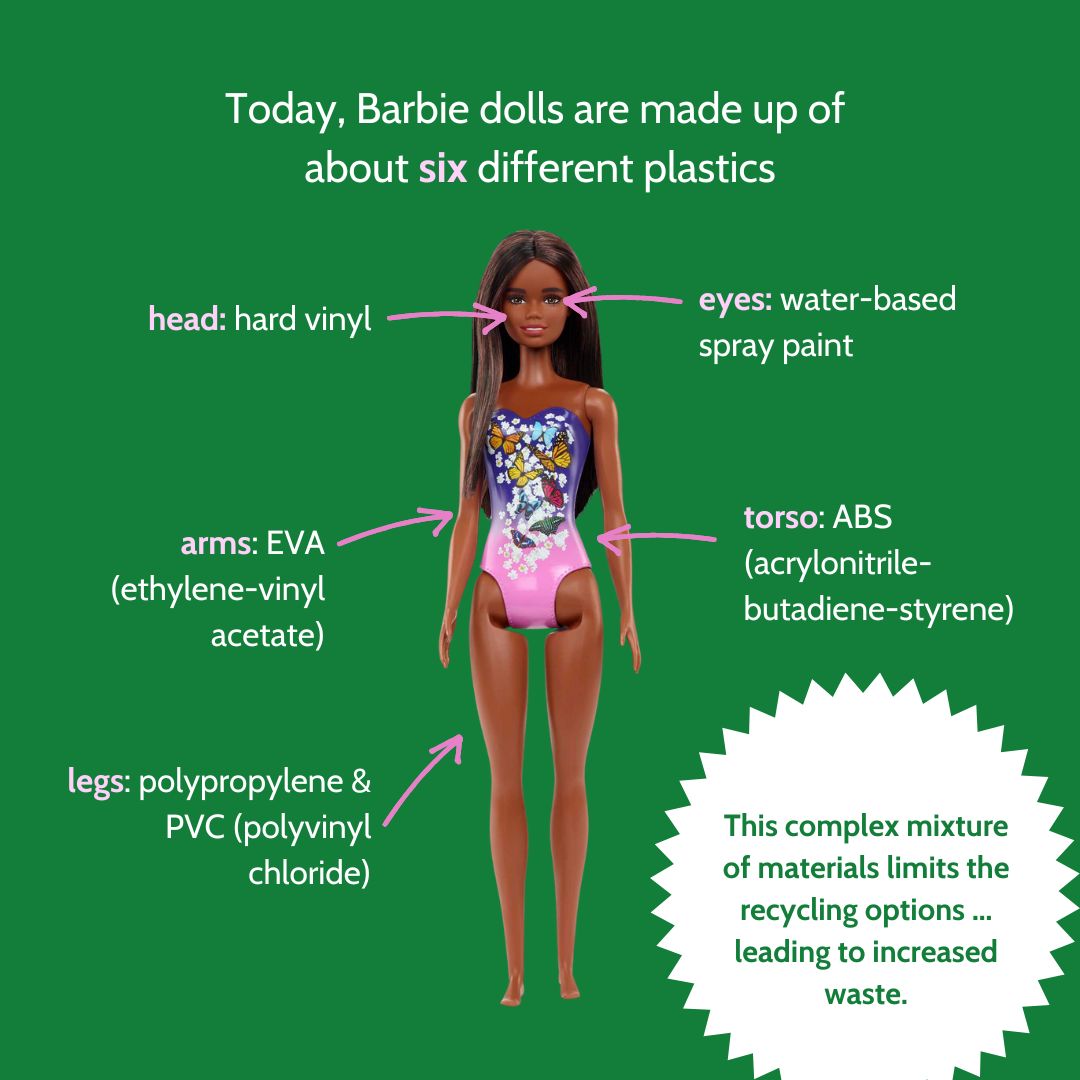

Plastic products (from dolls to sneakers to tires) are often essential to modern life, but harmful to the planet and human health. Most plastics are made of fossil fuels—gas, oil/petroleum—and a cocktail of chemical additives known to cause a variety of serious health problems. Additionally, plastic contributes to global warming, damages the environment, contaminates oceans, and harms marine life (Gordon, 2023; Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023). In the case of Barbie and all of her plastic “friends” and accessories, they are made with at least six different types of fossil-fuel-based plastics: (1) polyvinyl chloride (PVC); (2) polypropylene; (3) ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA); (4) acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS); (5) hard vinyl; (6) water-based spray paint; and additive chemicals (Plastic Reimagined, 2024).

One of these plastic additives, called Di(isononyl) cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylate (DINCH), has been used in newer Barbies to replace phthalates—additives linked to asthma, metabolic disorders, obesity, and other health problems. Research on human cells suggests DINCH could have adverse outcomes similar to other toxic plasticizers in children’s toys. Plastic toys also release toxic microplastics and nanoplastics, which are easily inhaled and ingested (especially if children chew on toys). Further, they off-gas volatile organic compounds (VOCs), linked to several health issues, including skin irritation, headaches, organ damage, nausea, and potential carcinogenicity. Children who chew on plastic toys risk absorbing dangerous chemicals, including lead, into their bodies. Plastics commonly contain hormone (endocrine) disruptors, which are linked to serious health problems including developmental, growth, metabolic, and reproductive issues. Plastic producers have not been transparent about the toxic chemicals they use in their products, including children’s toys. Research suggests that plastic toys made before 2007, particularly those made of PVC plastic like Barbie, are very toxic. Even after 2007, any type of plastic remains harmful to human health (Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023).

Plastics are dangerous even before they become plastics. They are made of highly toxic ingredients. Mass-produced children’s toys like Barbie may appear pretty, pristine, shiny, and polished, but they ultimately pollute air, food, water, oceans, soil, and bodies. This pollution starts when fossil fuel ingredients used to make plastics are extracted from the Earth and continues throughout plastics and chemical production, storage, transportation, and manufacturing. Plastics continue polluting throughout their use and eventual toxic “disposal” in landfills, incinerators, or the environment. When Barbies or other plastic toys are no longer desired or break—including their plastic packaging—they are often not recyclable (plastic was not designed to be recycled). Plastic pollution is responsible for approximately 9 million premature deaths per year (1 in 6 deaths) globally (Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023).

Plastic Fast Fashion Clothing

Many textiles—including those Barbie wears—contain plastic, which sheds from synthetic textiles into the air and waterways when washed. Polyester clothing, for instance, can shed up to 700,000 microplastic fibers during a single wash. In total, just washing clothes releases 500,000 tons of microfibers into the ocean each year—an amount equal to 50 billion plastic bottles. These fibers, which can take up to 200 years to decompose, pollute the ocean and eventually enter the food chain. One-third of primary microplastics released into the environment originate from washing synthetic textiles (The Squid Studios, 2024).

Cotton is a more natural and biodegradable fabric, but it carries its own toxicities. Cotton farming often involves heavy pesticide use. Conventional cotton cultivation is also extremely water-intensive. The high demand for cotton has led to unsustainable farming practices and labor exploitation. Viscose, the popular plant-based silk replacement, is often believed to be a sustainable alternative to cotton or polyester. Although viscose could be produced sustainably, high demand leads to harmful production practices. Wood pulp is treated with aggressive chemicals to obtain viscose yarn—a highly polluting process. Handling the chemicals leads to birth defects, skin conditions, cancer, and various health issues. Its chemical waste contaminates nearby water and farmland (The Squid Studios, 2024).

Mass-production of plastic fast fashion clothing generates wastefulness, as clothes are rapidly bought and discarded for newer items. Beyond the environmental damage caused by producing and using fashion items, most (87%) newly bought clothes are burned, end up in landfills, or are piled up in deserts (The Squid Studios, 2024). Fast fashion and the culture of consumerism in the Global North produce massive amounts of textile pollution disproportionately shipped to the Global South, where it causes dangerous pollution and injustice. Further, toys are commonly produced in the Global South by exploited women and youth who receive low wages to work in hazardous conditions for long hours—often without breaks. Pollution from these factories poisons downstream communities (Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023).

Looking like a Barbie doll has become appealing and trendy, particularly due to the Barbie film release. “Barbiecore is soaring,” according to Time Magazine (Lang, 2023). As mentioned, Barbiecore is the aesthetic of early aughts: bubblegum-pop, bright, pink—embodying stereotypical ideals of quintessential, unapologetic girlhood. This fad correlates with a time of unprecedented consumerism, from toys and video games to fast fashion, single-use plastic items, and other kinds of plastic pollution (Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023).

Demographics Affected by Plastic Pollution

Low-income, rural, women, youth, Black, Indigenous, and people of color communities are the groups most likely to be affected by plastic pollution. They often live on the frontlines of plastic and petrochemical industries, as well as near storage, transportation, and disposal sites and infrastructure, which greatly impact their health due to extreme pollution, noise, and light pollution. This diminishes quality of life and increases the risk of dangerous fires and accidents for these communities (Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023).

Current Efforts to Reduce Plastic Waste

United Nations (UN) negotiators are trying to reduce the explosion of plastic waste by focusing on reusing and recycling. The goal is to cut plastic waste by 80% by 2040. Further, several countries formed the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution, which advocates for global standards and restrictions on certain types of plastic. However, some groups, including major oil and gas producers, are pushing for countries to set their own goals in national action plans rather than following UN guidelines. Considering that 20% of global oil could be used to make plastic by 2050, global standards could be hugely important for the future of fossil fuel extraction and associated greenhouse gas emissions (Gordon, 2023).

The toy industry is recognized as the most plastic-intensive consumer goods market in the world, according to the United Nations Environment Program Report (Pearls, 2023). In the United States alone, 90% of toys are made of plastic components. Most toys cannot be recycled due to the complex mixture of materials used, making recycling economically unfeasible. For companies like Mattel, this non-profitable route is not appealing (Plastic Reimagined, 2024).

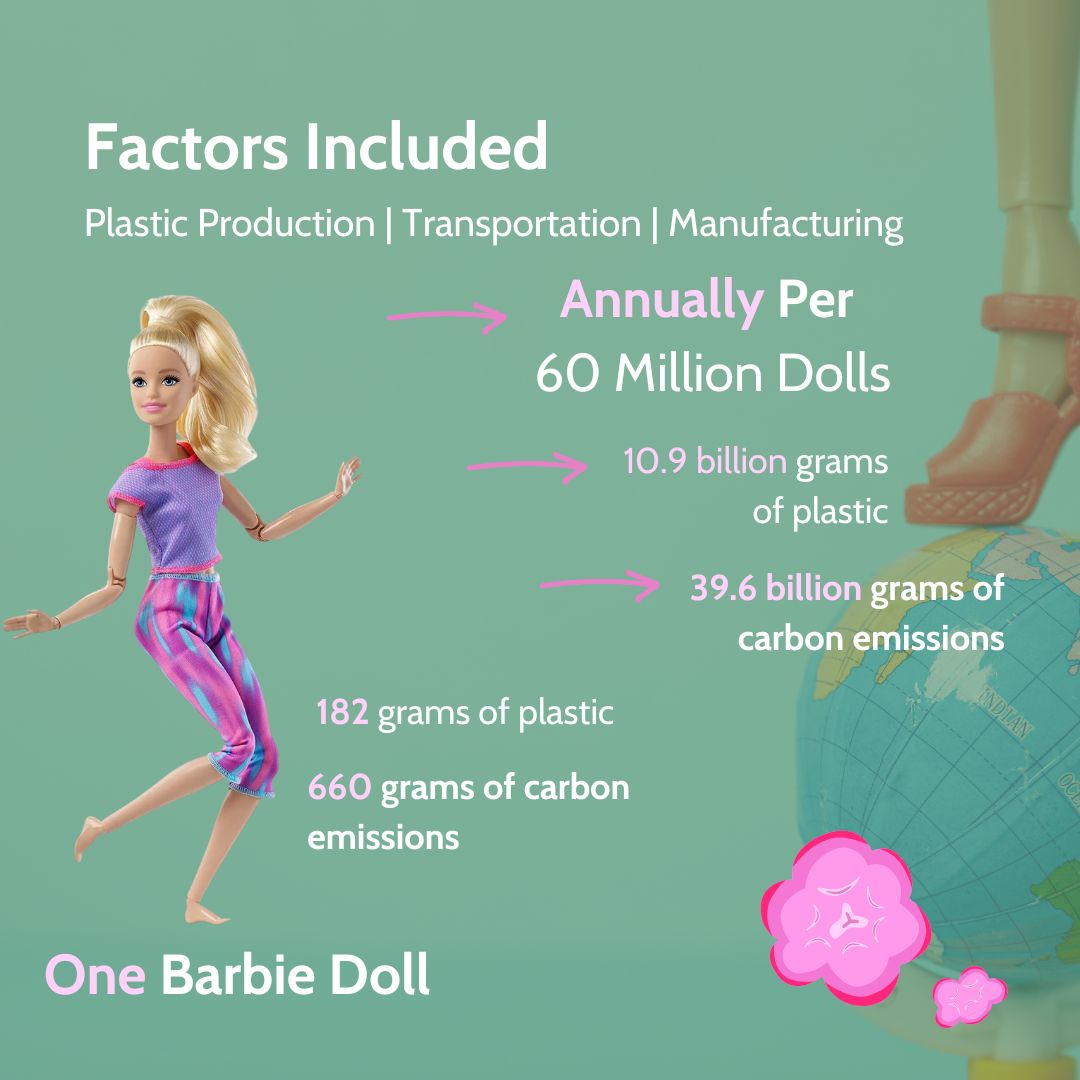

Since Barbie was created in 1959, Mattel has sold an average of 60 million Barbies annually, as demand for the doll has remained steady among young girls hoping to embody Barbie’s beauty. However, the Barbie film’s release triggered an even greater wave of doll purchases beyond this number. Specifically, buying multiple dolls when one does not need all of them has increased plastic use. Following the Barbie film’s success, the doll industry is expected to rise to $14 billion by 2027. These sales come with a large amount of plastic waste (Pearls, 2023; Shaw, 2023).

Carbon Emissions of Plastic and Fashion

Plastic’s impact on oceans not only kills marine life but also causes ocean acidification, reducing the oceans’ ability to absorb carbon. Healthy oceans absorb 25% of all carbon emissions and capture 90% of the excess heat generated by these emissions, according to the United Nations. The more plastic in the waters, the less carbon they can trap. With the release of the Barbie film in 2023 and the explosion in pink-themed sales, more Barbie products entered into global markets, increasing plastic waste and contributing to climate change (Ettinger, 2023).

Carbon emissions are also linked to fast fashion. The textile industry accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions. Approximately two-thirds of all textile items are now synthetic, dominated by petroleum-based polymers such as polyester, polyamide, and acrylic. Plastic microfibers and nanofibers have been identified in ecosystems across the globe and are estimated to comprise up to 35% of primary microplastics in marine environments. They persist for decades in soils treated with sludge from wastewater treatment plants. Once purchased and used, these items are notoriously difficult to recycle due to the combination of multiple materials (Henry, Laitala, & Klepp, 2019).

According to Ecoveritas (an environmental consultancy firm), a search for “Barbie” on the online fashion store Depop shows almost 20,000 results, with under half of the items labeled “unused” and “like new.” The top five labels in this search are all fast fashion brands that released “Barbie” product lines following the film’s success. There were over 100 brand collaborations for the Barbie film—the highest number of partnerships for any movie (Waldeck, 2023).

Despite the obvious effects of increasing synthetic garment waste on biodiversity and the environment, the ethical repercussions are many. The film states that “Barbie is all these women. And all these women are Barbie.” Feeding into the schemes of fast fashion brands contradicts the film’s entire message of uplifting unheard voices (Rucha, 2023).

Is Barbie a Step Towards Sustainability?

From a sustainability perspective, Barbie dolls have potentially contributed to huge amounts of waste, as one doll alone accounts for 182 grams of plastic along with approximately 660 grams of carbon emissions when factoring in plastic production, manufacturing, and transportation. Mattel is thus utilizing about 10.9 billion grams of plastic and producing 39.6 billion grams of carbon emissions annually for this product (Plastic Reimagined, 2024). These carbon emissions do not consider the entire Barbie universe, which includes other plastic Barbie items such as houses, cars, airplanes, friends, and more. Approximately 92% of American girls aged 3–12 own an average of 12 Barbie dolls, which translates to 7,776g or 7.8kg of carbon emissions per child (L., 2023).

Mattel has started noticing the environmental impact of the toys it produces. It aims to use 100% recycled, recyclable, or bio-based plastic for its products and packaging by 2030. In 2021, Mattel launched a range of Barbies made of recycled plastics. The following year, the company collaborated with the Jane Goodall Institute to release carbon-neutral-certified Barbies crafted from recycled ocean-bound plastic (L., 2023). Also, in 2021, Mattel introduced the “PlayBack” program, a recycling scheme that allows customers to send back old toys for repurposing. Attempting to develop a circular economy, Mattel is now paving the way for other toy companies to follow suit and move forward in an eco-friendly manner (Plastic Reimagined, 2024). While this can be applauded, recycled plastic does not necessarily negate the toxicity of the products or the adverse effects of plastic on biodiversity and people (Rucha, 2023).

Ideally, Mattel would adopt other healthier and more sustainable approaches, as seen in other toy companies such as BUUF, De Krokodil, Lunabloom, and various secondhand stores. Consumers could also purchase from smaller and local brands. They would not only be getting more sustainable products, but also contributing to the local economy, thus bringing myriad positive environmental effects automatically (Rucha, 2023).

Pink to “Sustainable” Green

Reducing the plastic footprint is not only beneficial for the environment but also for the companies doing it. Companies with such programs may be eligible to earn plastic credits. Each plastic credit equals one ton of plastic waste that would otherwise not have been collected or recycled. Companies can further leverage plastic credits along with carbon credits to address their sustainability concerns (L., 2023).

In a smart marketing move, a global challenge dubbed #NaturallyCuriousJane encourages young minds to adopt environmentally conscious activities like community mapping and amplifying green spaces. Barbie’s digital footprint (via its YouTube channel) showcases Dr. Jane Goodall, ensuring that her legacy and teachings ripple through younger generations (L., 2023).

Plastic-Free Barbie Hoax

The Yes Men, known for climate pranks, created a hoax announcing a “plastic-free Barbie.” A faux ad featuring climate activist Daryl Hannah aimed to draw attention to Barbie’s plastic footprint, especially after the Barbie film’s release. Since 1959, over 1 billion Barbies have been sold globally, with 60 million dolls sold each year. Responding to the hoax, Mattel noted that the company has long announced its sustainability goals, specifically aiming for 100% recycled, recyclable, or bio-based plastic materials by 2030. Part of these goals also involves reducing plastic packaging by 25% per product and achieving zero manufacturing waste (L., 2023).

Plastic Toys Last Forever

While gaming toys have dominated the market in recent decades, producing e-waste streams, this shift likely caused the longer-term decline in the popularity of plastic toys (Pearls, 2023). Toys were not always made of and packaged in plastic. Before the 20th century, most toys were made of glass, metal, or wood, and dolls were usually made of cloth. After World War II, mainstream plastic mass-production toys rose, including Barbie, Lego, Mr. Potato Head, and GI Joe. These replaced cloth, glass, metal, and wooden toys through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Currently, an estimated 90% of children’s toys are made of plastic due to its durability, versatility, and perceived “safety” (Plastic Pollution Coalition, 2023).

To cut through feelings of branding and consumerism, Greta Gerwig (Barbie film director) included clips of cast and crew’s friends and family in Barbie. “It’s like sneaking in humanity to something that everybody thinks is a hunk of plastic,” she told Time Magazine (Dockterman, 2023).

Barbie Doll Sales Also Increasing Severe Deforestation in Indonesia

Barbie also became a hot topic after the release of its first live-action film regarding deforestation. It revived discussions about the doll’s paper packaging and the issue of cutting down trees. In 2011, Barbie received strong protests over the use of paper packaging made from mixed tropical hardwood. The paper came from cutting down virgin forests, including the Sumatran Forest. Not only Barbie (Mattel) but also other companies use this material. GREENPEACE filed a protest through Ken’s campaign, asking him to break up with Barbie because he did not want a girlfriend involved in deforestation. GREENPEACE activists staged a protest after conducting field research and forensic tests on Barbie’s packaging (Saraswati, 2023).

This deforestation problem greatly affected Barbie’s image, prompting the company to improve the sustainability of its manufacturing system. Barbie cut off cooperation with packaging suppliers who engaged in deforestation and instructed suppliers not to use wood from virgin forests (Saraswati, 2023).

Furthermore, Barbie replaced the main material for making dolls by utilizing recycled ocean-bound plastic waste in cooperation with Envision Plastics, an HDPE plastic waste recycling company. Recycled plastic waste material is collected from plastic waste in the Baja Peninsula, Mexico (Saraswati, 2023).

Barbie Mania Isn’t Going Away Anytime Soon

Barbie and plastic go way back. Since the 1950s, when both were introduced, more than 8.3 billion metric tons (9.1 billion U.S. tons) of plastic have been produced, and 80% of all plastic ever produced still remains in landfills or scattered throughout the environment, according to the Earth Day organization. “Just like Barbieland, our planet is surrounded by plastic everywhere we look” (Ettinger, 2023).

Our Responsibility

As Greta Gerwig stated, “sometimes these movies can have a quality of hegemonic capitalism” (Dockterman, 2023). Many who played with Barbie and other plastic toys growing up may feel nostalgia for these items and their generational culture. Despite all the glamour of Barbieland and Barbie’s global cultural influence, the plastic she is made of and the wastefulness she encourages carry ugly truths. Ironically, Gerwig’s film itself received the Environmental Media Association (EMA) gold seal, indicating that the cast and crew practiced heightened sustainability measures behind the scenes and throughout production (EMA, 2023).

The EarthDay organization states that it is impossible to “decouple the glorification of plastic and its direct relationship to environmental and health degradation. While the Barbie movie has fans looking at a ‘life in plastic’ through rose-colored glasses, the reality is a lot less ‘gorgelicious,’” especially when considering the inequities within communities affected by plastic pollution. Marginalized and low-income populations are disproportionately affected by plastic pollution at every step of its lifecycle (Ettinger, 2023).

According to EarthDay, to shift the world away from a plastic “paradise,” collective action is needed from governments, industries, and individuals. “As an individual, it is your responsibility to make the consumption changes necessary to limit your plastic usage” (Ettinger, 2023).

Fashion Waste

The public has been focusing on the waste from Barbie doll sales. These plastic dolls are packaged with layers of plastic. According to Erin Gilchrist, a research intern at Ecoveritas (an environmental consultancy firm), criticisms are more focused on the plastic waste created by the dolls themselves and how the film increased this waste by boosting doll sales (Waldeck, 2023).

The Barbie movie is certainly not the only film loaded with merchandise. A concern for environmentalists is that the Barbie movie’s huge marketing and economic success likely sets a precedent for future films (Waldeck, 2023).

As argued by Gilchrist, it is hard to measure the waste that the Barbie film created. The problem of hyper-consumption and the negative environmental impacts that this consumption creates is also not mitigated. Film promotions could include reminders and practical tips to consume less and more responsibly, making environmental sustainability a priority when purchasing. Of course, this is neither the goal of the movie industry nor the merchandise deals behind it (Waldeck, 2023).

Currently, sustainable brands are pushing their pink and pastel-colored collections to the forefront. The eco-underwear brand The Big Favorite recently introduced a “Better Barbie” collection made with mineral dyes and cotton. “The Big Favorite’s vision for the future is simple: clean, iconic basics that don’t compromise for our customers or the planet; that means no compromise on color either,” founder Eleanor Turner said in a statement. “With the upcoming release of the ‘Barbie’ movie, we knew there was a better way to offer the iconic hot pink color that Barbie is known for without the harsh chemical dyes or synthetic fabrics. We were able to use a special non-azo, mineral-based dye that is low-impact, biodegradable, and eco-friendly on our 100-percent plastic-free Pima Cotton basics,” she continued (Ettinger, 2023).

What can be done to help?

Clothing Libraries and Sustainable Fashion

If people feel that “in-your-face pink” is not their everyday color, but they still do not want to miss out on showing their support for this Barbie-inspired feminist movement, they could consume through “the clothing rental business.” Renting an outfit from clothing libraries (such as Lena Library or WAUWcloset) offers vast options in Barbie-style clothing, though there are more options globally than in the United States. For minimalist and sustainable Barbie clothing, consumers can purchase high-quality clothing from places like Capsule Studio or Colorful Standard, and get vintage Barbie looks from SeventyOne, Oxfam, or Vintage Jungle, and luxury secondhand clothing from De Ruilhoek (Rucha, 2023).

Regarding shoes, if consumers are looking for Birkenstock, this brand can be found at PURE mechelen or a similar brand, Asportuguesas, or at Zappa Antwerp. More sustainable eco-vegan brands like Zouri or Baabuk from any of the Supergoods stores are also available (Rucha, 2023).

Fashion and Plastic Recommendations

How to identify (and avoid) fast fashion brands when shopping online or in-store:

- Rapid production (i.e., are new styles launching every week?)

- Trend replication (i.e., are styles cheaply made versions of recent fashion show trends?)

- Low-quality materials (i.e., synthetic fabrics, poorly constructed garments made to last only a few wears)

- Manufacturing locations (i.e., is production happening where workers receive below living wages?)

- Competitive pricing (i.e., is stock released every few days and then steeply discounted if it doesn’t sell?) (Stanton, 2024)

European and American bans on BPA-containing plastics in infant milk bottles illustrate what can be done to move toward a more sustainable world and reduce plastic (including toy) usage. Governments can set up effective recovery and recycling systems able to handle toys. Further, some plastic-dependent brands such as Lego are moving away from petrochemical-based plastic in favor of sugarcane-based plastic, though it is not a short-term project (Pearls, 2023).

While Barbie dolls had an uptick in popularity (e.g., during the pandemic years) and will undoubtedly have another surge alongside the movie (there are rumors of a Barbie film #2), longer-term trends are dampening the impact of plastic toys (Pearls, 2023). Mattel, the manufacturer of Barbie, is trying to clean up its plastic use. By 2030, its goal is to use 100% recycled, recyclable, or bio-based plastic in its toys and packaging (Gordon, 2023). But there are many ways consumers can promote sustainability or adopt more environmentally friendly practices when shopping for toys or jumping on the Barbie pink fashion trend. For instance, they should:

- Invest in durable, long-lasting toys

- Buy toys made of simple materials to streamline recycling

- Send damaged toys back to the manufacturer for repair

- Prioritize secondhand toys and pink outfits to find something unique and vintage

- Shop for quality pieces that can be worn multiple times rather than supporting fast fashion

- Choose sustainable fabrics such as organic cotton

- Support ethical fashion and toy brands

- Create pink Barbie outfits with a DIY approach

- Utilize toy recycling programs carried by many companies (i.e., Lego, Hasbro). These programs reduce landfill waste by around 50%; water consumption by 15%; energy consumption by 20%; and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 20% (D’Souza, 2023; Hasbro continues its sustainability, 2018; Plastic Reimagined, 2024).

Although toys have entertained children and adults for hundreds of years, consumers must exercise caution in how they use and dispose of them. Acknowledging the environmental impact of toys is critical to changing how the planet is affected (Plastic Reimagined, 2024).

Embracing slow fashion should be the new trend, especially when movie marketing strategies contribute to fast fashion consumerism. Marketing campaigns could offer alternatives with mindful manufacturing (i.e., including vertically integrated and in-house production), advocating for fair labor rights, natural materials (i.e., cotton), and long-lasting garments. Consumers should look for brands, communities, and individuals fighting for the planet and the safety of garment workers, as well as consumers’ health. Customers could purchase garments from responsible brands or shop secondhand, thus supporting and advocating for the environment (Stanton, 2024).

Similar to the fashion industry, consumers generally remain unaware of most details behind Barbieland, aside from the pretty and attractive exterior. Behind the pink clothes lies a dark side of the consumption industry that requires more transparency. Using the feminist message of the movie as a metaphor for underlying issues, there are many environmental, ethical, and social concerns—ranging from environmental impact and the ethical treatment of garment workers to plastic pollution—that should be observed and addressed before they proliferate (Rucha, 2023).

Furthermore, not giving in to fast fashion brands can be a small step toward making a difference in how these box-office movies are marketed and supported. The Barbie film is not the first to have a ton of associated merchandise, and it won’t be the last. These brands have an opportunity to promote sustainability through their promotions. As mentioned, it might have been a missed opportunity by Mattel, which could have encouraged people to follow sustainable ways of dressing up for the movie (D’Souza, 2023).

Works Cited