Street Harassment

is abuse that is so normalized that even brands and media accept it. Learn how to stop it.

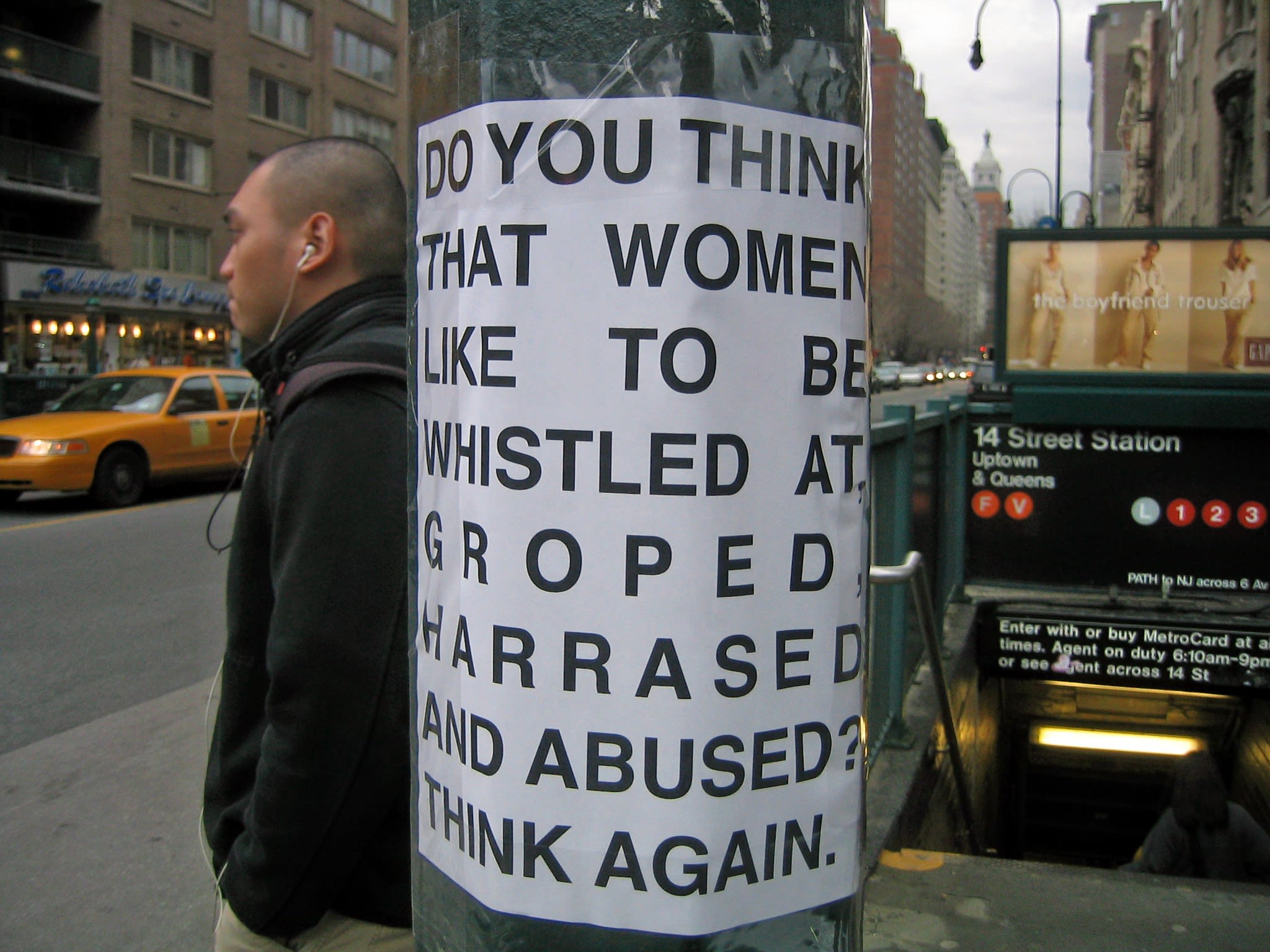

Street harassment is so prevalent that it is often considered trivial and harmless. But it’s a form of sexual abuse that intersects racism, homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of abuse.

What is street harassment? It is hard to clearly define street harassment as a category of behavior, given that there are many approaches used to conceptualize or coin the term. Additionally, there are debates in literature that have implications about how street harassment is understood, and how it should be addressed (Vera-Gray, 2016a, 2016b). “Street harassment” is a relatively new term that expresses the harm that individuals experience in the public sphere and that can be understood by others. It is complicated to find a term that adequately reflects the varied perspectives of street harassment, sometimes referred as “public harassment,” “sexual harassment,” or “stranger harassment” (Tuerekheimer, 1997; Wesselmenn & Kelly, 2010). Some scholars argue that harassment occurs across many public, semi-public, private, and digital spaces, and therefore, it is not limited to the streets (Vera-Gray, 2016a, 2016b).

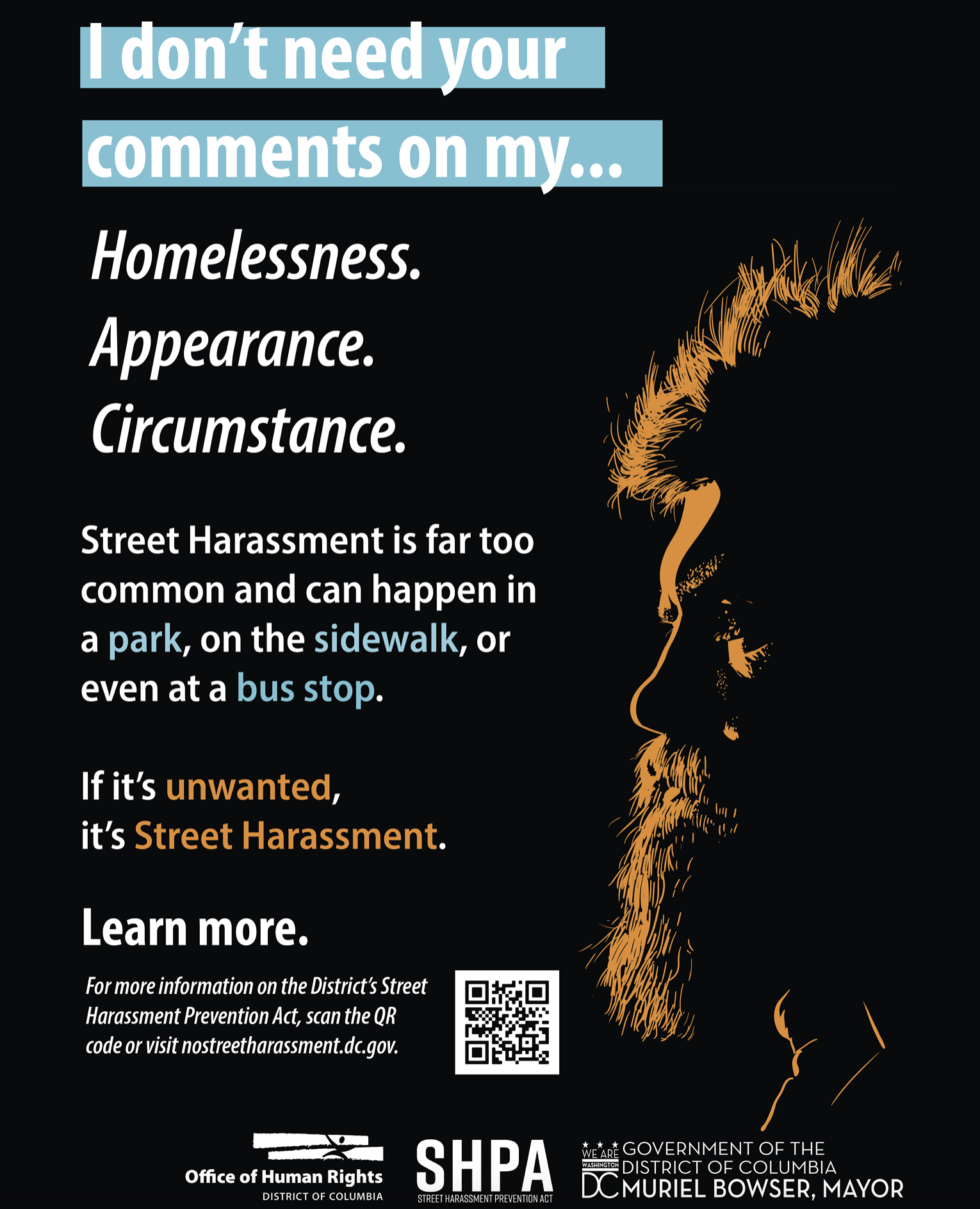

The Street Harassment Prevention Act of 2018 defines street harassment as any disrespectful, offensive, or threatening statements, gestures, or other conduct directed at an individual in a high-risk area.

This includes all public spaces and entities outside of a private residence – a school, bank, health care facility, mall, stores, theaters, restaurants, parks, sidewalks, bus stops, and so on) without the individual’s consent and based on the individual’s actual or perceived protected trait identified in the D.C. Human Rights Act of 1977. The Street Harassment Prevention Act of 2018 (SHPA) is a first of its kind legal measure in the United States. It was designed to uniquely focus on prevention through education instead of criminalization (Office of Human Rights, n.d.).

Street harassment represents one of the most pervasive and prevalent forms of sexual violence. While it is commonly understood as a gender-based harm, it also intersects with racist, homophobic, transphobic, and other forms of abuse. Despite its apparent commonality, street harassment has frequently been positioned as a “trivial” or harmless occurrence (Vera-Gray, 2016a). Therefore, it has received minimal attention in both research and policy. Although it is rarely addressed through government policy, research shows that street harassment can have profoundly negative impacts of those who experience it (Fileborn, & O’Neill, 2023).

Gender-based street harassment is defined as unwanted comments, gestures, and actions forced on a stranger in a public place or sphere without their consent. This harassment is directed at a person because of their actual or perceived sex, gender, gender expression, or sexual orientation (Stop Street Harassment, 2023). Many anti-street harassment activists overtly recognize the intersectionality of gender-based street harassment with other forms of harassment and other structures of oppression (Stop Street Harassment, 2021).

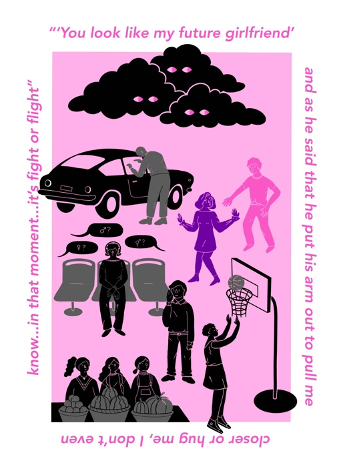

Examples of street harassment include unwanted whistling, leering, sexual and racist remarks, threats, stalking, homophobic or transphobic slurs, general intimidation, and persistent requests for someone’s name, number or destination after the harassment was ignored. It escalates to sexual names, comments and demands, flashing, public indecent exposure or public masturbation, groping, sexual assault, and rape. In many ways, street harassment is an act that forces an individual or individuals into an unwanted interaction where they become defined primarily as a sexual object or are reminded of their vulnerability in public spaces (It is not a compliment, n.d.; Stop Street Harassment, 2023).

Ad by Lucy Activewear spotted at a shopping mall which shows a woman bending over, wearing yoga pants, with the words: “Let the compliments begin. Try the new perfect booty pant.” The ad reduces women to their body parts (in this case, butt) and perpetuates the idea that women always dress to impress men and to receive compliments,” even when they are exercising.

Ad by Lucy Activewear spotted at a shopping mall which shows a woman bending over, wearing yoga pants, with the words: “Let the compliments begin. Try the new perfect booty pant.” The ad reduces women to their body parts (in this case, butt) and perpetuates the idea that women always dress to impress men and to receive compliments,” even when they are exercising.

Street harassment, or sexual harassment faced in public spaces, is a serious global problem, with research indicating that 80-100% of women globally have experienced some form of street harassment (Beswick, 2018; UKGEO, UK, 2021). For instance, Delhi, infamously known as the “rape capital” of India, is notorious for both verbal and physical harassment on public transportation (YouGov, 2014). 95% of women aged 16-49 report feeling unsafe in public spaces in India (UN, n.d.). Women incur significant psychological costs from sexual harassment (Langton & Truman, 2014) and actively take precautions to avoid such confrontations. In India, the majority of women aged 40 or younger said that they avoid certain areas in their city because of harassment (Livingston, 2015). Another study in India found that 75% of women had their first encounter with street harassment between 14 to 21 years of age (Borker, 2018).

According to a nationally representative survey in the United States, 65% of women have experienced street harassment (Stop Street Harassment, 2014), and 78% of women in the country have been followed by a man or group of men, making them feel unsafe. Additionally, many U.S. women have been groped or fondled without their consent (Gay, 2015). In South Asia, the euphemism “Eve teasing” downplays legitimate street harassment. Calling it “teasing” renders the practice innocuous while the invocation of “Eve” blames the victim, placing responsibility onto women for beguiling men into harassing them (Ramasubramanian & Oliver, 2003). In Latin America, a “piropo” is an allegedly “flirtatious, admiring compliment.” “Piropos” are so ingrained in Cuban culture that some state that women consider “a day without a ‘piropo’ to be ‘a wasted day’" (Lundgreen, 2013, p. 7). The Japanese term “chikan” describes both the men who grope women and girls in public and the prevalent practice of groping or uninvited sexual touching (Horii & Burgess, 2012). A Japanese survey showed that almost 2/3 of women in their 20s and 30s had been groped on Tokyo’s train and subway (Fairchild & Rudman, 2008, p. 339). Similarly, 86% of women living in cities in Thailand, and 86% in Brazil have been subjected to street harassment in public (Action Aid, 2016).

Despite cultural variation in how street harassment is perpetrated and experienced by women, all share similar approach, and the harassment becomes accepted as normal and invisible as a social problem. Specifically, it becomes invisible as a security problem (Fileborn & Vera-Gray, 2017, p. 205).

Typologies of street harassment

The terminology used to describe street harassment varies across studies, cultures, and countries. For instance, there are terms such as “men’s intrusions,” “public intrusions,” “street remarks,” “public incivilities,“ and “eve teasing” that are used across the literature by different researchers (Vera-Gray, 2016b). Public harassment against LGBTQ+ individuals and racist harassment may be labeled as “hate crimes” rather than harassment. Similarly, street harassment is a diffuse category and can refer to forms of sexual harassment and violence that take place on public transportation or other public spaces such as nightclubs, streets, schools, restaurants, and others (Fileborn, & O’Neill, 2023).

Street harassment is a broad array of behavior, and there is ambiguity in terms of what actions “count.” The most common approach classifies street harassment as a form of sexual harassment that is overwhelming perpetrated by male strangers against women in public space. This typically includes actions such as catcalling, kissing noises, horn honking, staring or leering, following someone, unwanted conversations (i.e., repeated requests for a date or phone number), sexualized gestures, frottage, unwanted touching, indecent exposure, and public masturbation (Brundson, 2018; Campos et al., 2017). However, some scholars have included behaviors such as physical abuse and violence, sexual assault, and rape (Armstrong, 2016; Campos et al., 2017). The boundaries around what “counts” as street harassment are blurred and varied.

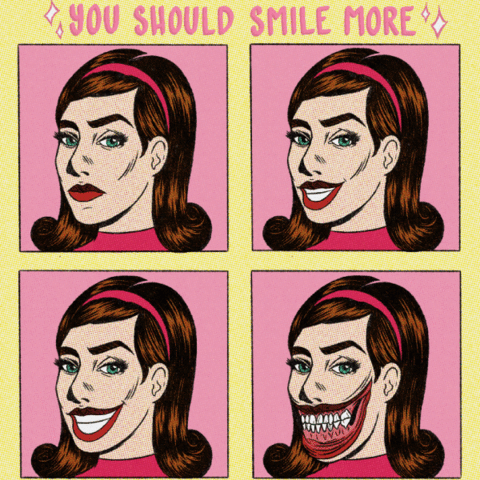

Establishing a typology of harassment is also complicated because what is lived or experienced as harassment in different cultures can be highly contextualized and subjective (di Gennaro & Ritschel, 2019; Farmer & Jordan, 2017; Vera-Gray, 2016b). Further, many forms of public harassment are not overly sexualized and may appear ambiguous, if not “friendly” in nature, when viewed as isolated incidents (i.e., commands to “smile” or greetings such as “hello” – see di Gennaro & Rischel, 2019; Vera-Gray, 2016a, 2016b).

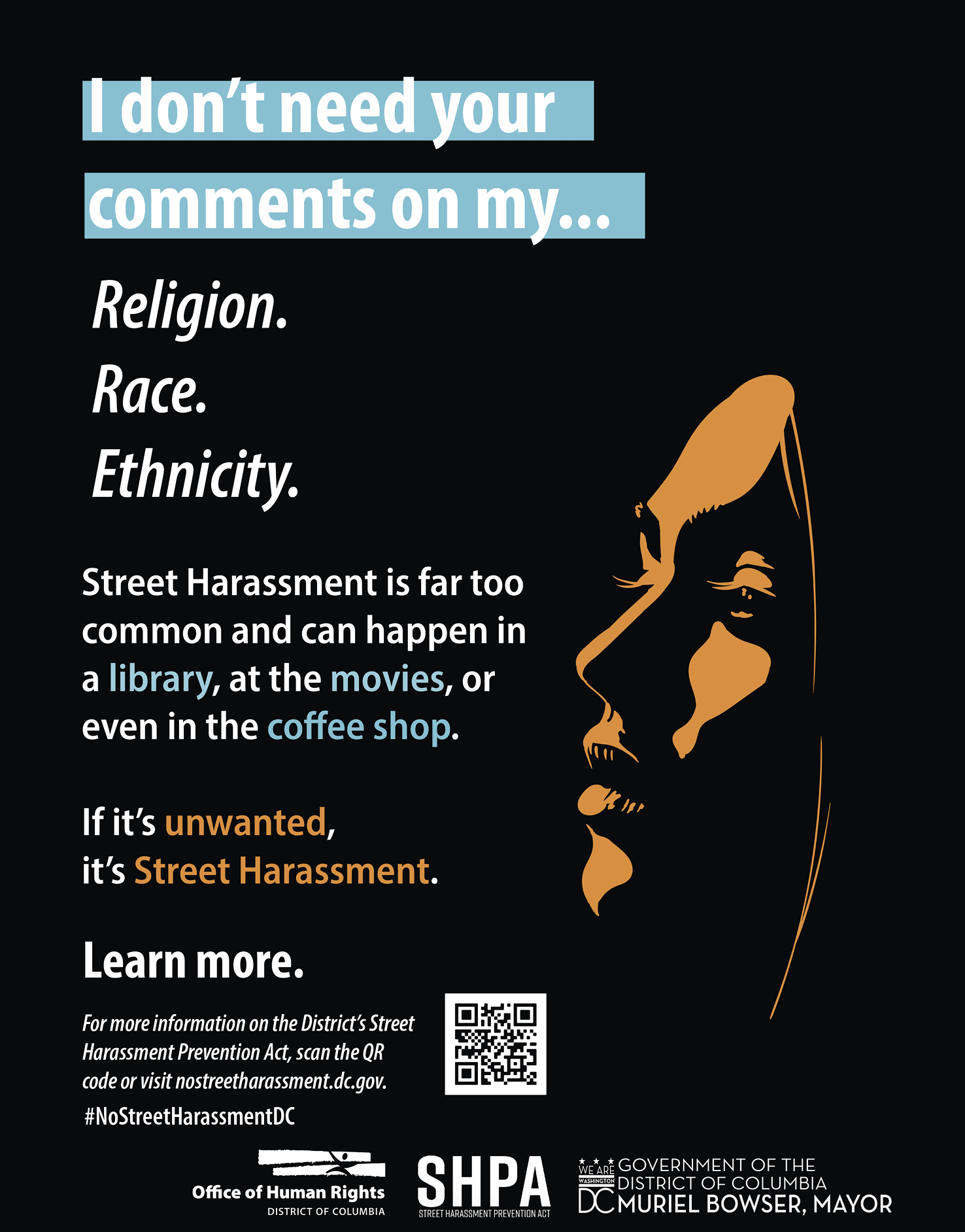

Typologies of street harassment must take into account how harassment is shaped through different (sub)cultures and perspectives. For instance, while street harassment is most commonly framed as sexualized, it can manifest in ways that are racist, homophobic, transphobic, ableist, Islamophobic, and so on (Chmielewski, 2017; Mason-Bish & Zempi, 2019). For Black, Latin, or Asian women, it is often not possible to separate racism from sexist harassment. Consequently, forms of street harassment can shift across different countries and groups, as well as filtered through the lens of personal experience, context, norms, and structures of power, religion, economy, and politics (Fileborn & O’Neill, 2023).

Who is harassed?

Anybody can be harassed on the street: from women to religious and ethnic groups to homeless people to LGBTQ+ community members. But according to some studies, in all countries, women, girls, and individuals from the LGBTQ+ community are the most vulnerable and fearful of being assaulted, threatened, or harassed by others. The highest level of fear relates to public spaces such as restaurants, public transportation, streets, parking lots, parks and others. The lowest level of fear occurs at home, work, and school, although affected populations are still aware that harassment can happen in any place. The most harmful and dangerous incidents usually occur when more than one perpetrator is involved, and the majority of the incidents tend to be inflicted by men that are strangers. Perpetrators’ age is not necessarily a barrier. Intolerance is a global characteristic, and no country or place is free of street harassment (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2013).

In 2019, NORC (National Opinion Research Center) at the University of Chicago conducted a national survey of 1,182 women and 1,037 men and found that 81% of women and 43% of men reported experiencing some form of sexual harassment (NORC – University of Chicago, 2019).

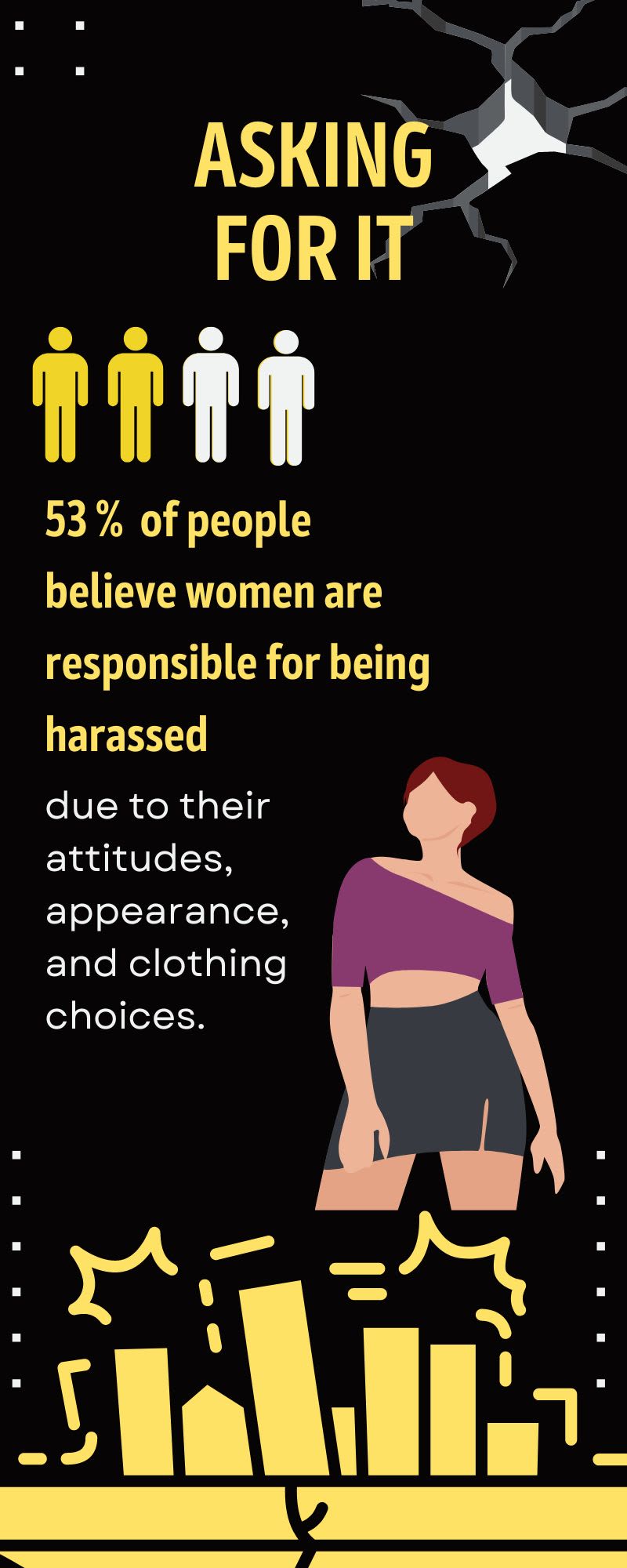

In the United States, a previous study conducted by Grow from Knowledge (GFK) in 2014, in a sample of 2000 nationally representative subjects, found the following (Stop Street Harassment, 2014):

- 65% of all women nationwide had experienced street harassment vs. 25% of men (a higher percentage of LGBTQ+ identified men than heterosexual men reported this, and their most common of harassment was homophobic or transphobic slurs (9%)).

- Globally, 80% of women have experienced sexual harassment in public spaces.

- 53% of people believe that women are responsible for street harassment due to their attitudes, way of dressing, and appearance.

- 86% of street harassment witnesses say there is a lack of training of how to intervene.

- Among all women, 23% had been sexually touched without consent.

- 20% had been followed.

- 9% had been forced to do something sexually.

- Half of harassed individuals were harassed by age 17.

In an informal international online 2008 study of 811 women conducted by Stop Street Harassment:

- 1 in 4 women had experienced street harassment by age 12 (7th grade).

- Nearly 90% had experienced street harassment by age 19.

Street harassment often occurs on a more frequent basis for teenagers and women in their 20s, and the chance of it occurring never disappears (Stop Street Harassment, 2023; L’ORÉAL, 2023).

While women also harass men in public, gender inequality is large. For women or individuals perceived to be female, the frequency of harassment is higher as is the underlying threat of rape, and the impact on their lives. Further, although public harassment might be motivated by racism, homophobia, transphobia, or classism (types of harassment in which men can be the target and sometimes perpetrated by women), it is socially unacceptable behavior, but men’s harassment of women motivated by gender and sexism is normalized. In fact, street harassment of women is often perceived and portrayed as “complimentary,” a joke, or only a “trivial annoyance.” Usually, society tends to blame women for its occurrence based on what they are wearing or what time of day they are in public (Stop Street Harassment, 2023).

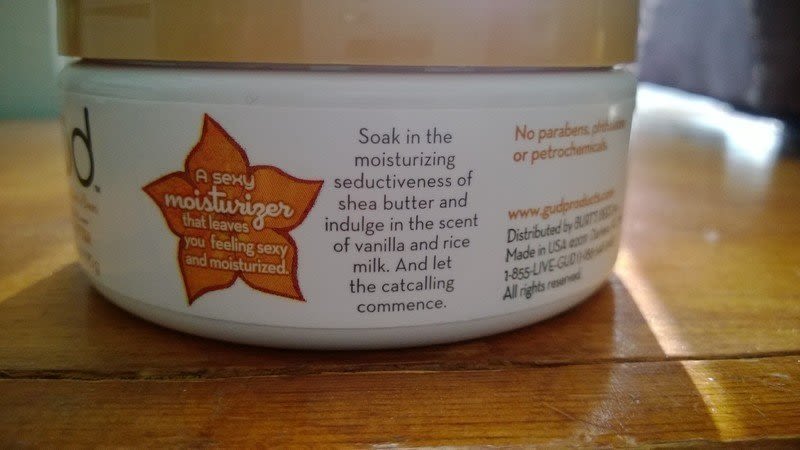

The package label on the Burt's Bees Güd Vanilla Flame Body Butter showed: “Soak in the moisturizing seductiveness of shea butter and indulge in the scent of vanilla and rice milk. And let the catcalling commence.” This encouraged street harassment and treated it like a compliment. After a change.org petition got nearly 2,000 signatures, Burt's Bees apologized and acknowledged that it legitimized street harassment. The label was changed once stock sold out.

The package label on the Burt's Bees Güd Vanilla Flame Body Butter showed: “Soak in the moisturizing seductiveness of shea butter and indulge in the scent of vanilla and rice milk. And let the catcalling commence.” This encouraged street harassment and treated it like a compliment. After a change.org petition got nearly 2,000 signatures, Burt's Bees apologized and acknowledged that it legitimized street harassment. The label was changed once stock sold out.

Why are individuals harassed?

There are several factors that may provoke harassment including race/ethnicity, nationality, religion, disability, economic class, and actual or perceived gender fragility, expression or sexual orientation. Some individuals are harassed for multiple reasons that happen in a single incident. Mobility of women, girls, and members of the LGBTQ+ community can be restricted by harassment and hateful violence (Stop Street Harassment, 2023). For instance, a 2013 study by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) reports the high level of discrimination that the LGBTQ+ demographic suffers in European countries. The report found that more than 93,000 LGBTQ+ members experience bias-motivated discrimination, violence, and harassment in different times and places (i.e., employment, education, healthcare, home). The 2013 study showed that 1/2 of respondents avoid public places, 2/3 avoid holding hands when in public, and 4/5 overhear jokes about their sexuality.

Summary of the EU LGBT survey

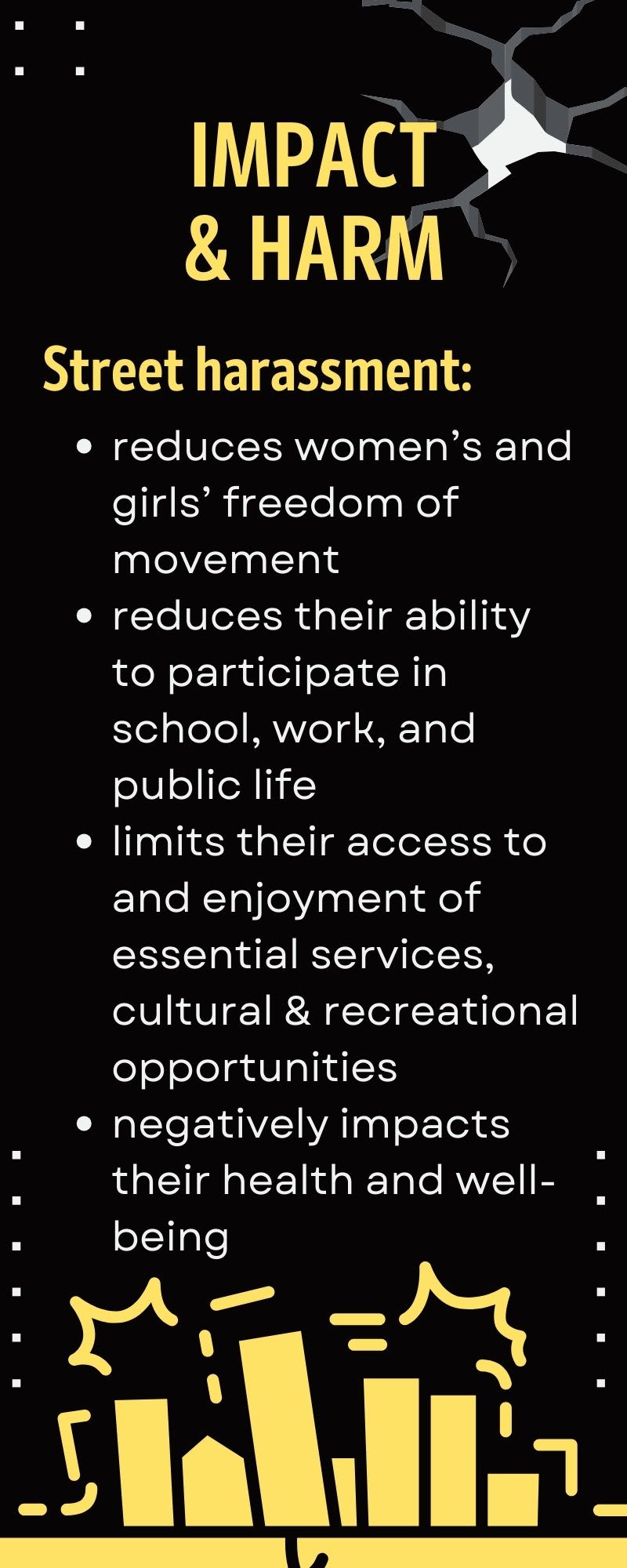

Impact and harm

Research in Western countries (i.e., United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia) shows that street harassment causes substantial harm to individuals who experience it (Bastomski & Smith, 2017; Betts et al., 2019). Studies from these countries report that experiencing street harassment increases women’s fear, anger, violation, depression, feeling of guilty, repulsion, and many other negative emotional and affective states (i.e., fear of further forms of sexual and gender-based violence occurring as a result) (Bastomski & Smith, 2017; Betts et al., 2019; Donnelly & Callogero, 2018).

Further, street harassment can impact women’s use of public spaces; that is, they avoid public spaces, unsafe areas, avoid the dark, move away from the harasser, and modify their behavior in order to enhance their sense of safety. A small number take no action to avoid harassment (Borker, 2018). There are studies reporting how intrusion shapes women’s embodiment. This type of impact can accumulate over time and can persist for days, months, and years. The severity of the street harassment impact is subjective and can be dependent on the context (Fileborn & O’Neill, 2023; Vera-Gray, 2018; Vera-Gray & Kelly, 2020).

Global impacts

The impacts of street harassment also vary across cultural contexts. For instance, women in Islam, Pakistan, India, and other East Asian countries go to public spaces only if they are accompanied by male family members, and many women and girls withdraw from education or may not attend school at all. Specifically, cultural gender norms combined with the patriarchal structure of society play a role in how women are impacted by and respond to street harassment (Adur & Jha, 2018; Ahmad et al, 2020; Bharucha & Khatri, 2018). Women also experienced increased fear and decreased autonomy upon their return back to their countries after living abroad, according Alcade’s (2020) study conducted with migrants in Peru. The same study found that women who returned as adults with children had their fears and anxieties shifted toward the safety of their female children.

Impacts and harms of street harassment differ according to survivors’ positions regarding gender, race, class, sexuality, and disability. For instance, individuals experience street harassment differently on the basis of the privilege that they occupy (Fileborn & O’Neill, 2023). Migration also greatly impacts women’s experiences of street harassment, particularly by shaping the autonomy that survivors have over their bodies. Muslim women who wear a veil in public increase their risk of experiencing street harassment in Western countries due to their hypervisibility in public spaces. Indeed, women are placed in situations where they must navigate their safety in public spaces by choosing what to wear, which may impact how they are perceived in their communities (Mason-Bish & Zempi, 2019).

Everyday insecurities

Street harassment produces a wide range of insecurities. These insecurities can undermine safety, livelihood and dignity. They can affect the individual and sometimes the community as a whole.

- Psychological insecurity – persistent fear and anxiety from feeling unsafe. Women in particular find street harassment more upsetting than men because of the fear of it escalating to sexual assault or rape. The fear of what an aggressor will do next gives any kind of harasser power. Even comments less explicitly threatening may be perceived as such because of their sexual content (Desborough & Weldes, 2023).

- Dignity insecurity – freedom from indignity, grounded in human rights of privacy, equality, inclusion, non-discrimination. These human rights are undermined by street harassment, which constitutes an invasion of privacy by treating individuals as public property and objectifying women, reducing their individuality, personality, identity, and accomplishments to mere body parts (Tuerkheimer, 1997).

- Political, economic, and social insecurity – similar to “ghettoization of women” by confining them to the private sphere, reducing their access to the public sphere. Street harassment produces second-order political, social, and economic insecurities by having women use coping strategies to deal with the problem (i.e., “dressing decently,” “coming back home on time”). According to a 2015 Australian report, 93% of women aged 18-24 years and 88% of women aged 25-34 years altered their behavior to prevent street harassment and assault. For instance, they avoided walking alone at night; held their keys in their hand as a weapon; or pretended to be having a conversation on their phone (The Australia Institute, 2015). Similarly, in Brazil, 97% of women reported changing their routes to avoid harassment and violence (Action Aid International, 2015). Some of these coping strategies have potential economic implications. For instance, in India, girls have been forced to drop out of school, with significant consequences for their life chances because of the prevalence of sexual harassment on buses and on school routes (Deswal, 2013). If women, girls, and other targets are too anxious, intimidated, or frightened to access public spaces, they may not be able to search for employment, commute to work, go to school, access public services, vote, or participate in political life (Abraham et al, 2015).

FIAT Super Bowl Ad - a TV commercial that compared a woman to a car that a man leered at and objectified. This commercial promotes the idea that women are objects for men to covet, leer at, and want to “own.” Further, it promotes the sexual objectification of women and makes light of and glorifies street harassment that women face in real life.

Tapbooty is a social app where users can gain rewards for playing trivia games and answering questions. Its ad on the Boston public transit system promotes touching women inappropriately. Boston asked MBTA officials to remove advertisements from some of their trains. It was perceived to promote the objectification of women and non-consensual touching. Further, the product received media coverage for the online activism on this issue, including in Boston Magazine. MBTA agreed to remove the ads from its transit system.

Tapbooty is a social app where users can gain rewards for playing trivia games and answering questions. Its ad on the Boston public transit system promotes touching women inappropriately. Boston asked MBTA officials to remove advertisements from some of their trains. It was perceived to promote the objectification of women and non-consensual touching. Further, the product received media coverage for the online activism on this issue, including in Boston Magazine. MBTA agreed to remove the ads from its transit system.

Lego created construction-worker themed stickers for children that included a construction worker saying: “Hey Babe,” presumably to a woman walking by. It is a message to children reinforcing that street harassment is acceptable, and a message to adults that street harassment is just light-hearted fun one can joke about. Additionally, the product perpetuates the idea that it is primarily construction workers who engage in street harassment and that all construction workers are street harassers. The public complained on social media. Lego apologized, removed the stickers from the market, and stated that the brand would not approve such a product again.

Lego created construction-worker themed stickers for children that included a construction worker saying: “Hey Babe,” presumably to a woman walking by. It is a message to children reinforcing that street harassment is acceptable, and a message to adults that street harassment is just light-hearted fun one can joke about. Additionally, the product perpetuates the idea that it is primarily construction workers who engage in street harassment and that all construction workers are street harassers. The public complained on social media. Lego apologized, removed the stickers from the market, and stated that the brand would not approve such a product again.

At the Nike Women’s Half Marathon in D.C. in 2013, Bare Minerals by Bare Escentuals enlisted a group of fraternity brothers to hold up inappropriate and sexist signs saying: “You look beautiful all sweaty,” “Hello gorgeous,” “Cute running shoes,” etc. The signs aimed to promote the brand’s “Go Bare Tour of America.” The signs reinforced sexism and told women that no matter what they achieve, no matter how athletic or fat they are, it is only their looks that matter. The company is telling men that it is okay to address sexist comments to women they do not know on the streets. Women runners endure a lot of street harassment and they should be able to run a race they trained hard for in peace. Many people voiced their displeasure over social media about the approach. Within a few hours, the company tweeted back apologizing and promised not to degrade women runners or support street harassment and objectification, and stopped using the sexist, pro-street harassment signs on their #GoBare Tour of America.

At the Nike Women’s Half Marathon in D.C. in 2013, Bare Minerals by Bare Escentuals enlisted a group of fraternity brothers to hold up inappropriate and sexist signs saying: “You look beautiful all sweaty,” “Hello gorgeous,” “Cute running shoes,” etc. The signs aimed to promote the brand’s “Go Bare Tour of America.” The signs reinforced sexism and told women that no matter what they achieve, no matter how athletic or fat they are, it is only their looks that matter. The company is telling men that it is okay to address sexist comments to women they do not know on the streets. Women runners endure a lot of street harassment and they should be able to run a race they trained hard for in peace. Many people voiced their displeasure over social media about the approach. Within a few hours, the company tweeted back apologizing and promised not to degrade women runners or support street harassment and objectification, and stopped using the sexist, pro-street harassment signs on their #GoBare Tour of America.

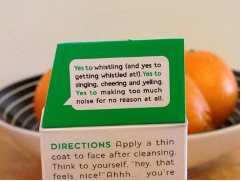

Yes to Carrots face wash packaging - The container of face wash promoted the idea that street harassment is something desired. The company is headquartered in the northern California, one of the only areas in the United States where street harassment has been studied. The study found that 100% of women had been harassed in public spaces – including whistling. Further, a few weeks before the product was spotted, a man stabbed a woman in San Francisco after she ignored his verbal harassment on the street. After social media protests, Yes to Carrots apologized for the offending statement and promised to change the packaging.

Yes to Carrots face wash packaging - The container of face wash promoted the idea that street harassment is something desired. The company is headquartered in the northern California, one of the only areas in the United States where street harassment has been studied. The study found that 100% of women had been harassed in public spaces – including whistling. Further, a few weeks before the product was spotted, a man stabbed a woman in San Francisco after she ignored his verbal harassment on the street. After social media protests, Yes to Carrots apologized for the offending statement and promised to change the packaging.

Reporting street harassment

There are barriers to report street harassment to the police and criminal justice system. Individuals who experience street harassment are reluctant to report to police as it can be another form of gender-based violence (Fileborn & Vera-Gray, 2017; Mullany & Trickett, 2018). A study in Australia shows that many individuals do not report street harassment to the police perceiving it as futile due to the trivial nature of what happened, being unsure as to whether the incident was illegal, believing there was nothing that could be done, and that the emotional and time-based costs of reporting was not worth the harm of the incident (Fileborn & O’Neill, 2023). The perceived insignificance and normalization of street harassment means that those who do not report to police the occurrence are most likely to fulfill the category of victim-blaming and inaction, which reduces the confidence of survivors in the police. Indeed, many think that most harassments are considered to be too minor to be reported (Boutros, 2018; Sheley, 2020).

Bystander intervention is reported to be rare (Fileborn & O’Neill, 2023; Vizvary, 2020). While bystander intervention could be successful in reducing or stopping the harassment, in some cases it could either escalate the harassment or it could be displaced onto the bystander. However, in many circumstances, bystander intervention could increase the victims’ sense of safety and reduce the perceived harm of an incident. It could also provide a sense of justice by holding the perpetrator accountable (Vizvary, 2020). However, bystanders can also be negatively impacted by witnessing sexist harassment such as catcalling, with women experiencing higher levels of anger and fear toward men (Fileborn & O’Neill, 2023).

Brands perpetuating street harassment

Street harassment is a serious problem that limits individuals’ access to public spaces. However, society as a whole still treats it as a joke, compliment, or no big deal. Commercial brands contribute to how this behavior is portrayed in ad campaigns. There is an ongoing list of corporations who trivialize street harassment in their ads or products. Here are some global examples of brand campaigns that normalize street harassment (Stop Street Harassment, 2023).

A sign spotted at MarketFair Mall in Princeton, NJ that reads: “We apologize for the whistling construction workers, but man you look good! So will we soon, please pardon our dust, dirt, and assorted inconveniences.” Sexual harassment in the workplace and in schools is illegal. Here is a mall encouraging construction workers to harass female customers. A petition and pressure from social media (and blogs such as Jezebel and Huffington Post), calls to the mall, resistance, and public outrage resulted in the removal of the sign.

A sign spotted at MarketFair Mall in Princeton, NJ that reads: “We apologize for the whistling construction workers, but man you look good! So will we soon, please pardon our dust, dirt, and assorted inconveniences.” Sexual harassment in the workplace and in schools is illegal. Here is a mall encouraging construction workers to harass female customers. A petition and pressure from social media (and blogs such as Jezebel and Huffington Post), calls to the mall, resistance, and public outrage resulted in the removal of the sign.

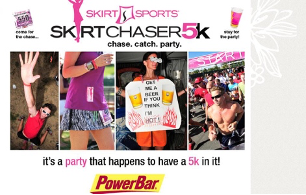

Skirt Sports - A 5K race called “Skirt Chasers” is where women start three minutes ahead of men and it is billed as a “party that happens to have a 5K in it.” The tagline was “Chase. Catch. Party.” The name and terminology of “catch” and “chase” is inappropriate. In a SSH survey of 811 women, 75% had been followed or chased (including abducted, raped, or murdered) in a public space by someone they did not know. This was considered a very scary form of street harassment. Social media and blogs (i.e., Jezebel, Huffington Post) created resistance and outrage from the public, resulting in the removal of the ad sign.

Skirt Sports - A 5K race called “Skirt Chasers” is where women start three minutes ahead of men and it is billed as a “party that happens to have a 5K in it.” The tagline was “Chase. Catch. Party.” The name and terminology of “catch” and “chase” is inappropriate. In a SSH survey of 811 women, 75% had been followed or chased (including abducted, raped, or murdered) in a public space by someone they did not know. This was considered a very scary form of street harassment. Social media and blogs (i.e., Jezebel, Huffington Post) created resistance and outrage from the public, resulting in the removal of the ad sign.

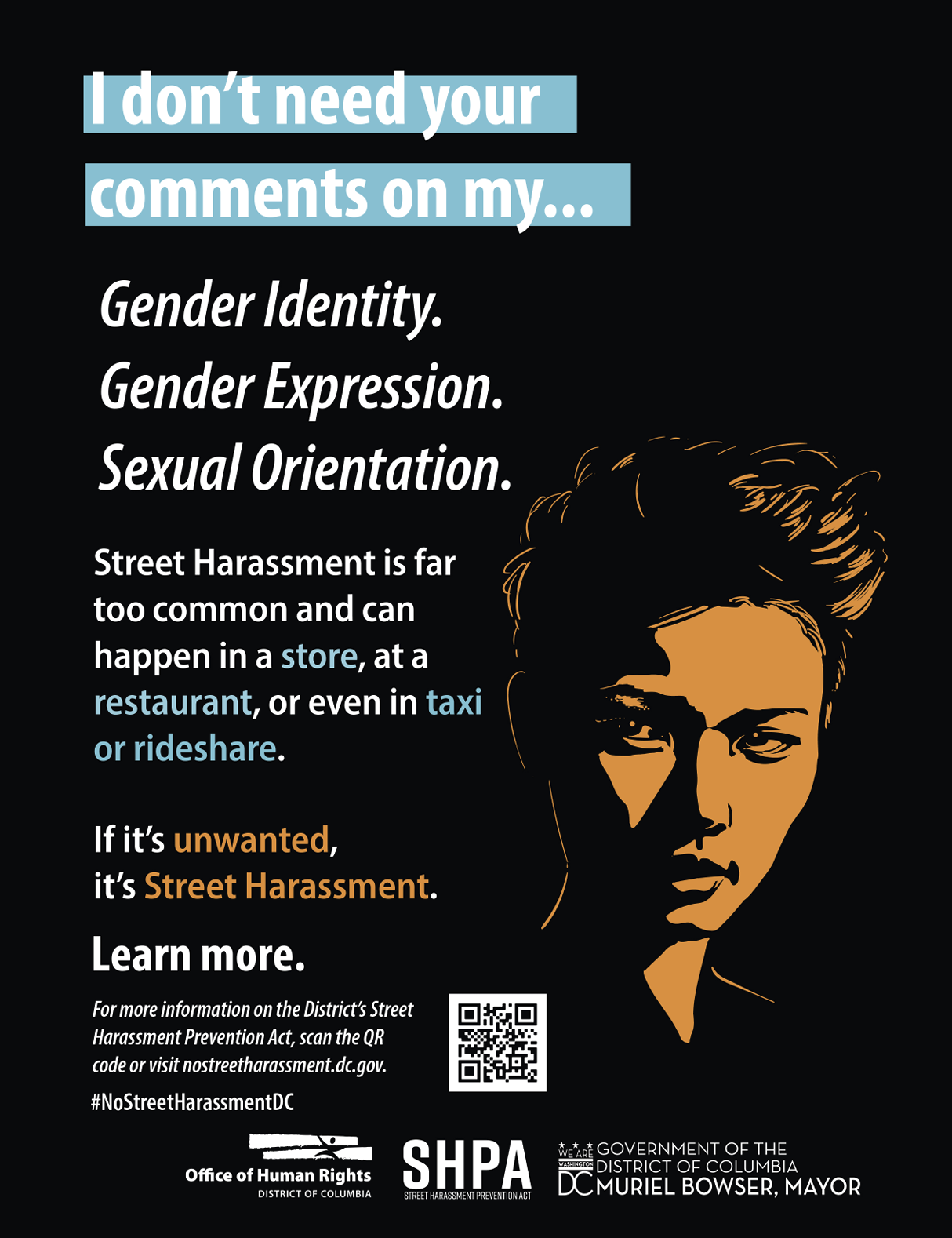

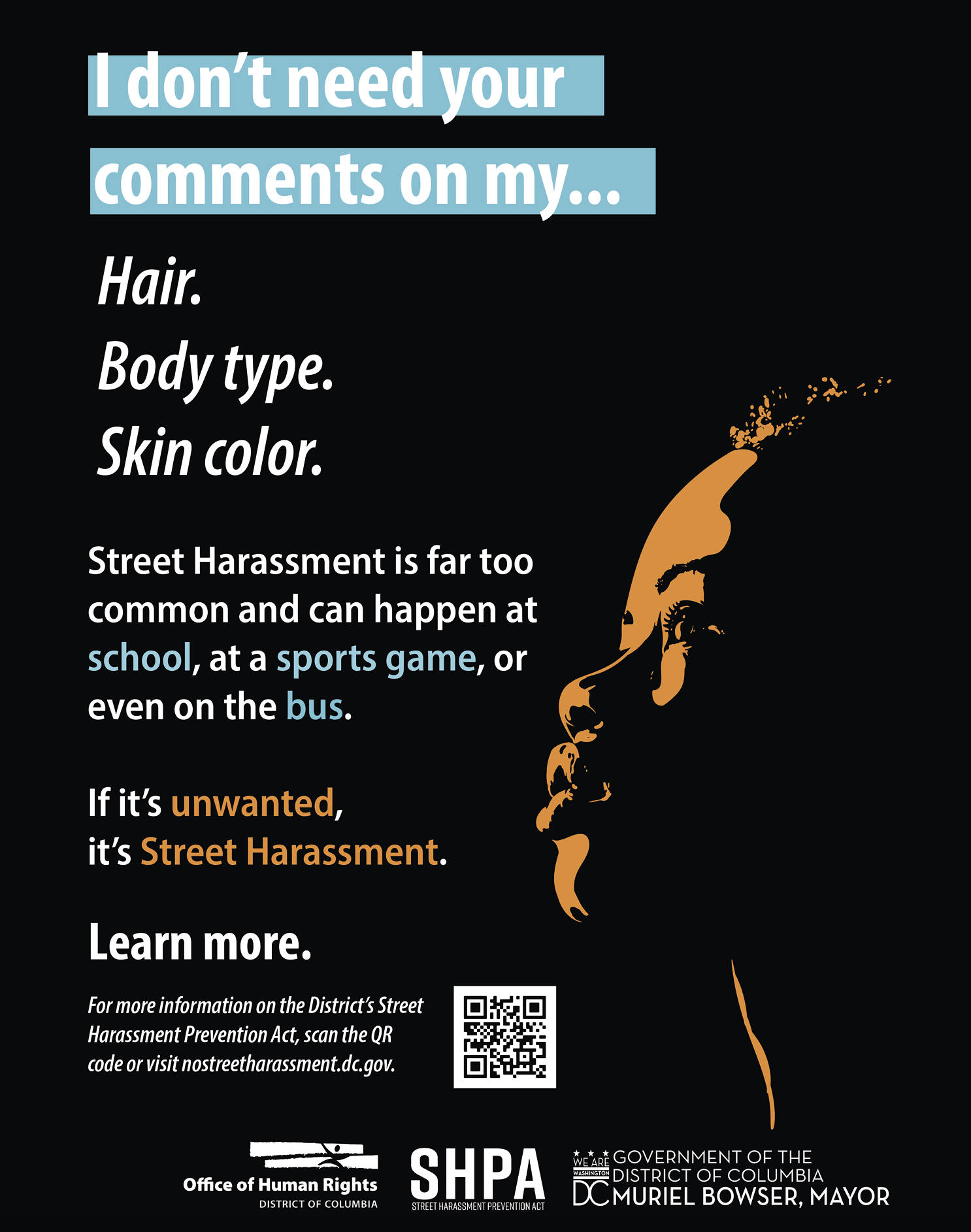

PSA campaigns standing up against street harassment

The No Street Harassment DC campaign (government-funded and developed by the DC Office of Human Rights) promotes awareness of the harm caused by street harassment, particularly the ones focused on vulnerable populations. The goal of this campaign is to reduce incidents of street harassment and increase understanding as to what street harassment is about and where it can occur (Office of Human Rights, n.d.).

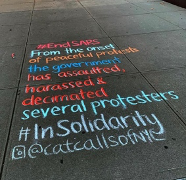

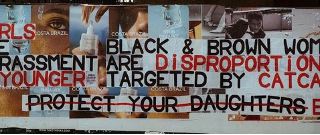

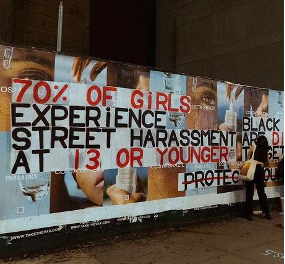

According to Yola Mzizi, founder of Catcalls of Chicago, “the reason why so many women and girls are catcalled and harassed everyday has, contrary to popular opinion, little to do with how we look or how we’re dressed,” As she stated, it has everything to do with power, misogyny and individuals’ desire to take away the bodily autonomy of women and girls. Mzizi is one of many women around the world mobilizing to end street harassment through social media and grassroots campaigns that address the root causes of the problem (Kirschner, 2022).

Catcalls of Chicago is part of “Chalk Back” – a social media movement started by Sophie Sandberg in New York City (and one of many social media accounts around the world which shares street harassment experiences (i.e., from Catcalls of Berlin to Catcalls of Bogota to Catcalls of Nigeria). Chalking their experiences of street harassment on the sidewalk where the harassment occurred, it is a way of raising awareness of the problem (Kirschner, 2022).

Put yourself in her shoes, instead of finding ways to blame her

This PSA was released by the UN Women’s Egypt country office. It invites men and boys to see what a day’s worth of street harassment looks like from a woman’s perspective. The slogan is “Put yourself in her shoes, instead of finding ways to blame her.” This PSA is part of the “Safe cities: Free from violence against women and girls” project, which recognizes that street harassment in public spaces is a serious problem (Feminist messaging project, n.d.).

The video starts with a woman in a cab, visibly uncomfortable at the way the driver is ogling her in the review mirror. She pulls her jacket around her, trying to cover herself up as much as possible to avoid this invasive gaze. The video then shifts to the viewpoint of another woman walking down a neighborhood street in broad daylight, harassed by a group of teenage boys who block her path. Then, we see through the perspective of a third woman getting on a crowded public transportation van. Within seconds, a man slides his hand onto her leg. She screams at the man, slaps him, and the other passengers start to react to her behavior; they do not appear supportive. The door of the van opens, and we see that she is the one expected to exit for making a fuss, and not her harasser. In the last scene, we see through the perspective of a woman being menaced by a group of grown men on the street at night (UN Women, 2013).

Mirror to street harassers in India

“Dekh Le,” an Indian anti-street harassment PSA video, shows men staring at women in various public spaces, while in the background, a Hindi song (Look how you look when you’re looking at me) plays in the background. The video shows staring/leering which is regularly minimized as something to which women and girls “overreact.” In the video, men’s stares are shown reflected back at them in mirrors that the women wear (reflective helmet, a necklace, sunglasses, and a mirror on a handbag). The men see their ogling faces and immediately turn away, ashamed of their behavior. This PSA video was released on December 16, 2013, the one-year anniversary of the horrific gang rape that was reported around the world, and more than a decade later, it still stirs feelings and sentiments amongst the audience (Feminist messaging project, n.d.; Whistling Woods International, 2013).

#IsThisOK – Gender-based violence & street harassment in the UK

“Our Streets Now” is a national campaign, started by sisters Maya and Gemma Tutton, aimed to make public street harassment illegal in England and Wales. “I think that we can all agree that feeling safe is a basic requirement to live your life,” stated Maya Tutton (Kirschner, 2022).

This campaign launched a petition urging the government to write and pass legislation making street harassment illegal. The petition has received over 400,000 signatures online (Kirschner, 2022).

Enough campaign to tackle violence against women & girls in the UK

An alarming 60-second TV ad shows how to help stop sexual harassment in the street, launched by the U.K. government to change a “lasting male attitude” toward women. The TV ad shows examples of street harassment, coercive control, unwanted touching, workplace harassment, revenge-porn and cyber-flashing that women put up with daily. According to the Home Office minister Rachel Maclean, “The only way to make successful change is to keep repeating our message that violence against women and girls will not be tolerated anymore. We’re working to change attitudes and behaviours within society so people notice the signs. We will not stop repeating enough is enough. We just have to keep sharing the message until attitudes finally change.” Home Secretary Priti Patel stated, “For too long, the responsibility of keeping safe has been placed on the shoulders of women and girls. This campaign says enough, and recognizes it is on all of us to demand major societal change. Everyone has a stake in this” (Adu, 2022).

In the United Kingdom, it is not a crime to sexually harass people in public, unless it leads to assault or another criminal offense. That is, there is no law that prevents catcalling, creepy behavior or other unwanted, threatening, and harmful advances. However, there are growing calls in the U.K. to change that. A new outdoor PSA campaign has been launched throughout a partnership between Our Street Now, a movement against street harassment that was launched I 2019 by sisters Gemma Tutton and Maya Tutton, and charity Plan International, a global children’s and girls' rights organization (Spary, 2021).

Postcards about people’s experiences of street harassment in Australia

The International Anti-Street Harassment Week (IASHW), started in 2011 by Stop Street Harassment, an organization that uses the voices and campaigns from around the world to fight for safer public spaces. This Melbourne (Australia) collects postcards about people’s experiences of street harassment and can be found in public spaces as well as in social media and audio content. It is part of a conversation and the search for a solution to stop street harassment (It’s not a compliment, n.d.).

Brands getting involved

Gillette: “We believe: the best men can be”

Released in 2019 by Procter & Gamble, the Gillette razor ad campaign was a support for the #MeToo movement, displaying masculine harassment towards women. In the commercial, both men and young boys are portrayed in aggressive manners. For instance, a man is shown in the ad groping a woman’s butt on live television while other men were laughing at it. The ad urges men to hold each other to a higher standard and to step up when they see fellow men acting inappropriately towards women. By being the culprits of harassment towards the female population, the ad strives to display the idea that men have the ability to change. Playing with “The best men can get” with “The best men can be.” However, the video has received intense criticism on social media with many men calling for a boycott of the brand (Guardian News, 2019).

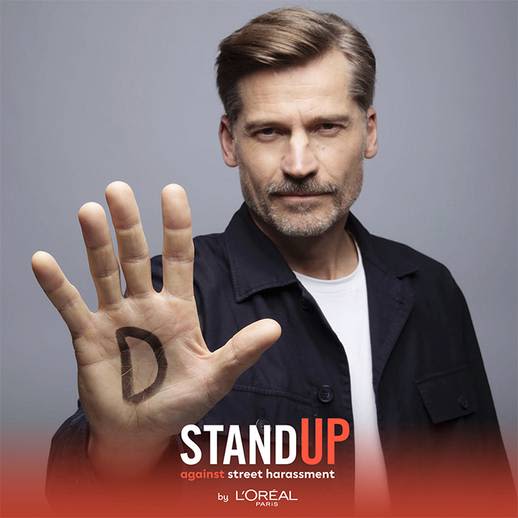

L’ORÉAL Paris and Right to BE

The French brand L'Oréal Paris launched its Stand Up campaign on March 8, 2020, in partnership with Right to BE (formerly Hollaback), an international nonprofit that fights against harassment of all forms. The campaign focused on raising awareness for the issue and training 1.5 million people using the “5D’s methodology.” The brand still invites the public to rally behind this cause and encourages them to get trained. As of 2022, 950,000 people have been trained with Stand UP across 41 countries (L’OREAL Groupe, 2023).

Guarded bus stop campaign in Brazil

The Brazilian government partnered with Eletromidia (the biggest out-of-home media company in Brazil) and launched a campaign against street sexual harassment titled Guarded Bus Stop. The initiative released videos on social media with the intent to prevent this type of crime. It received the Gold Lion award at Cannes Festival 2023 (Agencia Brasil, 2023).

The campaign is about an advertisement service that keeps company digitally and in real time with a potential victim, who is waiting for her bus at late night to go home. Eletromidia analyzed the bus stops in one of the more populated cities of the country and mapped those which are more dangerous and deserted for women to be alone. The company then provided a billboard with microphone, touch screen, full HD night vision camera, and presence sensor. This sensor detects when there is only one person in the bus shelter. The person can touch the screen and start a video call with a professional from a surveillance company.

Ghadi detergent in India

Ghadi detergent, a brand under the RSPL conglomerate, launched a campaign showing street harassment faced by women in India when stepping outside in the time of Holi. The campaign, “Is Holi, saare mael dho dalo?” takes on miscreants who take advantage of “bura na mano holi hai,” which translates to “don’t be offended; it’s just holi,” and touch women without their consent. The television commercial urges women not to hold back but stand up to someone who tries to apply color without her consent in the street. The campaign is also supported by digital, outdoor, and print media, and was released in 2017.

In summary, street harassment is not only about sexism. It can involve racism, classism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, and other forms of structural oppression. Street harassment can happen to anyone anywhere in the world. However, it is predominantly targeted toward women (It is not a compliment, n.d.; Stop Street Harassment, 2023).

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights emphasizes the importance of stopping street harassment, and calls for nonprofits and education systems to embrace the cause, develop more research, and educate individuals from early ages. Street harassment is a critical issue in the lives of many women and the LGBTQ+ community (European Union, n.d.).

Although there are already groups working to address other forms of harassment (i.e., racism, homophobia, transphobia, or classism), there are few addressing gender-based harassment (Stop Street Harassment, 2023).

Gender-specific constraints

Gender-specific constraints may explain the economic mobility differentials between men and women in developing countries. These constraints include laws that limit women’s access to and ownership of productive assets (Rakodi, 2014), poor access to credit (Asiedu et al., 2013), and women bearing disproportionate responsibility for household work (Ferrant, Pesand, and Nowacka, 2014).

Street harassment is a serious problem around the world, especially in rapidly urbanizing developing countries. While there is qualitative evidence on the negative effects of street harassment on women’s economic mobility, there is not much quantitative evidence to assess the long-term economic consequences of street harassment. For example, a study reported in India, with route mapping from Google Maps and mobile app safety data, shows the trade-offs women face between college quality and travel safety, relative to men. Women face significant trade-offs and are willing to attend a college that is 25% lower in the quality distribution for a route that is perceived to be safer. On the contrary, men are only willing to attend a college that is 5% lower in the quality distribution for a route that is safer. The same study found that women are willing to spend additional money on annual travel, relative to men, for a safer route. These results show that on the labor-market earnings advantage from attending college, women’s willingness to pay for safety translates to a 20% decline in the present discounted value of their post-college salaries. Thus, street harassment is an important mechanism that could perpetuate gender inequality in both education and lifetime earnings (Borker, 2018).

There are other economic decisions made by women that could be affected by their propensity to avoid harassment. For instance, the global labor force participation rate for women is 26.7% points lower than the rate for men in 2017 and the largest gender gap in participation rates is faced by women in emerging countries (World Employment Social Outlook, 2017).

Global fight against street harassment

Anti-street harassment movements developed specifically because there is little done by many countries' governments to consider street harassment a “serious security” issue, and therefore, there is little effort to combat it. Lack of policies and laws that can address security practices suggest that countries need to rethink disciplinary boundaries to protect their individual citizens independently of gender, race, economic class, age, and others (Desborough & Weldes, 2023).

Governments should create “safe spaces” where harassment is overtly considered unacceptable (i.e., creating a “zero tolerance” society or align with businesses to sponsor or improve spaces that are typically hostile everyday settings). Businesses should get involved in these movements by providing or sponsoring strategic (awareness) campaigns. This type of approach would help women and others to have access to everyday spaces and activities that are often dangerous or unpleasant (Desborough & Weldes, 2023).

Steps to address and prevent street harassment

Here are some steps that everybody can take to help in situations of street harassment (It is not a compliment, n.d.; Regina, 2012):

- Actively listen when someone shares their story: Keep in mind that it is difficult for anyone to disclose their experiences of harassment. Provide compassion and state that it was not their fault. Ask if there is anything you can do to help, and let them know you are there to support.

- Distract the harasser: This is the best way to intervene when you witness a street harassment incident. It can be done simply by coming in between the target and the harasser or creating some sort of commotion to allow the target to leave the scene.

- Fake friendship with the target: Just going up to the target and saying “hello” could disengage the harasser.

- Bring it home: Try saying something that would make the harasser understand the consequences of his actions (i.e., “I hope no one speaks to you like that” or “What if someone treated your girlfriend/sister/mother in that way?”)

- Take a picture: Depending on where you live, taking pictures of harassers (if you feel safe doing so) can be an effective way to stop street harassment. Sharing photos of the harasser during or after the act can be a strong deterrent. Make sure it is legal in your area.

- Take control and learn how to respond to your harassers: Confronting individual harassers or talking back to harassers with an assertive, forceful response can be disconcerting to the harasser, and negate the gender power imbalance of a harassing behavior. It shows that the harassee is neither a passive object nor a hysterical victim. And it also creates an environment that makes it more difficult for harassers to harass. However, make sure to use your instincts on whether or not a response might lead to an escalating situation.

- Call the police: Call the police, especially if you feel direct involvement or intervention would be unsafe. The police can do what is necessary or remove the harasser(s) from the environment.

- Ask for directions or the time: A great way to direct attention away from the target is to ask a random question. You can ask the question either to the harasser or to the target. Either way, the presence of a third party can make a difference in stopping street harassment.

- Accidently spill your drink: This would be a way for bystanders to intervene – to accidentally spill a drink/coffee/etc. Most likely, it is not something that the harasser would feel compelled to react against, but gets the message of disapproval across.

- Visible disapproval: Looking disapprovingly at the harasser or murmuring something loud enough so that the harasser can hear will help the harasser to realize that this behavior is not acceptable to the public. It can also help the target feel supported.

- Report the harassment: In some situations, it is possible to report a harasser or harassing behavior. Reporting a harasser could discourage the person from harassing anyone in the future. Keep in mind that harassing behaviors such as indecent exposure, stalking, and assault are illegal in some jurisdictions, which facilitates law enforcement involvement. Street harassment is hugely underreported, which makes it difficult for activists and policymakers to understand how pervasive the problem is.

- Do your research: Educate yourself about street harassment and the wide range of individuals affected by it.

- Have conversations that challenge the normalization of street harassment: If your friend/family or someone you know catcalls on the street, or says that street harassment is not a problem, remind them that it can impact the lives of many individuals. Take time to explain to them why their behavior is inappropriate. Step away from the group if they are engaging in harassment to show your disapproval.

- Get uncomfortable: Challenge your own biases, acknowledge your privilege, and consider how this has affected your experiences. Be open to understanding how street harassment can affect individuals from marginalized communities (i.e., women, LGBTQ+ members, and individuals with a disability or a race different from your own).

- Share your own experiences: If you are comfortable, raise awareness of street harassment by speaking about your own experiences and the realities of moving through public space. If you have not experienced harassment but witnessed it or have been an active bystander, share about this too.

- Share educational content: Spread awareness of street harassment by sharing content from activists and organizations (i.e., on social media). Make sure to uplift the voices of those from marginalized communities.

- Call out victim-blaming when you see it: in the media, from family, friends, and those around you. For instance, harassment is not caused by what someone is wearing, the time of the day, or whether the individual is alone.

- Make your presence known: A creative way to intervene is to make your presence felt. This will make the target feel safer and also discourage the harasser, especially in isolated areas or at night. For instance, you can cough or talk loudly on the phone.

- Be an active bystander: Of course, when it is safe to do so, intervene in instances of street harassment (when you see it happening). Check in with the targeted person afterwards. A simple act such as this can be helpful and validate to someone who has experienced street harassment.

- Get a group together or talk to fellow bystanders about intervening: If you feel that intervening alone would be unsafe or futile, start talking to individuals around you. Try to get a group together to intervene. This may deter the harasser and can also encourage other individuals to become effective allies in the fight against street harassment.

- Organize a community audit: Get together with your community and complete an audit of your neighborhood and the ways in which public safety could be improved (i.e., more lighting or better incident reporting systems). Present the outcomes to your local government and encourage local-level changes.

- Join an anti-street harassment group or organization: Advocate against street harassment. Volunteer or join groups around the globe. Engage with online activism or start your own group.

- Be a role model: Be a good role model to individuals around you, especially young men. People learn from everyone around them and if you set a good example, many will follow.

Works cited: Street Harassment References